Sunday, June 30, 2019

Top Secret DNA Mission:

Creating Your Private Tree

Sometimes, a researcher just needs a sandbox to play around with those genealogical experiments. No, I'm not talking mad scientist here; just a tucked away spot where we can test our hypotheses about those DNA matches we never knew were part of our family tree.

Before I get into the specifics, let's look at a few reasons why a public tree is usually a good option. Prime purpose, of course, is to serve as cousin bait: to attract those distant cousins out there who might have inherited all the "goods" from great-great-grandma Smith. The idea is collaboration and sharing, something many avocational genealogists are delighted to do. Besides that, think of public trees as a way of sharing that contributes toward the greater genealogical good, whether as a trailblazer on an obscure line of your family, or to feature an overlooked document which supports your case about a certain ancestor.

It's no surprise that companies which serve the genealogical community are strong advocates for sharing trees publicly. After all, that's what likely inspired the start of their business. And it's the choice given to subscribers as a default on sites like Ancestry.com.

Public trees, however, are not always the best choice for the individual subscriber. I have heard fellow researchers mention that they have switched their tree from public to private, expressly for the purpose of luring those cousins they've baited into divulging their interest: if a tree is viewed publicly, who's to know it has been seen at all—or by whom? A private but searchable tree still can alert other researchers to the presence of a possible cousin, but doesn't show the goods without sending a message to contact the subscriber, requesting the tree to be shared.

Some trees include sensitive information that the researcher might not want to share with everyone. That reason can be behind the choice to make a tree private for a wide variety of reasons—everything from just preferring to be a private person to being someone needing to experiment by plugging in alternate choices for names and relationships, like an adoptee seeking birth parents. The thought that, in the midst of this experimentation, another researcher can come along, spot the (mis)information, and replicate it in her own tree may be alarming to a conscientious researcher.

In the case I discussed last week, I had a similar reason for wishing to create a tree and make it private—and unsearchable: I have a set of DNA matches in whose trees is shared one particular surname, one which I have never encountered in researching my paternal grandfather's own family history. Obviously, I want to build a tree so I can play around in that genealogical sandbox and experiment with relationships; I think so much more clearly about such things when I can draw diagrams and pedigree charts. But equally as obvious, I certainly don't want someone stumbling across my family history scribblings and lifting those notes as gospel truth. That would instigate replication of error, something I certainly wouldn't want to cause.

So, the question is: just how do we go about setting up such a tree? Here is a quick demonstration of how to do a private, unsearchable tree on Ancestry.com for those who might want to do this someday. Keep in mind that any Ancestry subscriber can set up several trees—I certainly have done so, especially in my photo-rescuing projects—but just realize that the default questions asked along the way often point the subscriber to setting up a public and searchable tree. In this case, we want to do exactly the opposite.

First step in setting up a new private tree: sign in to your Ancestry account and head to the home page. There, look at the header bar across the top of your screen. It looks something like this:

Then, hover your cursor over the second choice on that header: "Trees."

Click on "Trees" and it will give you a drop-down menu. Scroll to the very bottom of that menu, looking for the choice, "Create & Manage Trees." That's the one you want to click.

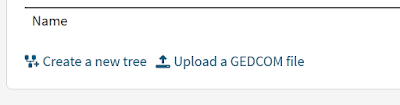

Once again, that choice will give you a list of trees. If you have just one tree, that's fine—others like me might see a list of more than one tree in their list. The point is to once again look toward the bottom of that list, where you will find the choice, "Create a new tree."

Once you click that "Create a new tree" option, it will lead you to a box labeled "Start a new tree." Inside the box is the outline of a pedigree chart—only there aren't any names included in the chart yet. That's where you start entering the details.

When you click on the brown box on the left, it will open up another page where you can start entering information on your "home" person. If this were your own family tree, of course you might enter your own name and start working your way back to your parents, but remember this is a different tree; you are building a tree to answer a question about someone else. In my case, this is where I entered the name of my closest match's deceased mother's name, because hers was the surname which I then found replicated in the trees of my more distant matches.

Notice at the top of this page how a box is pre-selected, stating "I am starting with myself." Uncheck that box if you are starting with another home person. Also note the default choices for gender (set to unknown and needs to be updated) and whether that person is living.

Whether you know a lot or a little about this person you are adding, no matter. Just enter what you can for now. Then click the green button on the bottom left labeled "Continue." The idea is to set up this experimental tree as quickly as possible and get started working on the family constellation. In my case here, even if I hadn't had other matches with that surname, I could have taken what information I already had on this woman and done a search on Ancestry for other supporting documentation. The key is that this was my toe-hold; this is where I could begin my search.

From that point, you can add a second name. Depending on the purpose for your search, that second name could be a spouse or a parent. It really doesn't matter; once you enter only two names, that triggers Ancestry's next step to officially set up the tree.

Once again, in adding this second person to your tree, pay attention to required data, such as the status of the individual, living or deceased. Once you click the green "Save" button on the bottom left of the screen, you are ready to set up your tree.

At this point, Ancestry wants you to name your tree. You'll notice they suggest a name—generally the surname you've already entered—but this is not set in stone. You are certainly welcome to change it. In my case, since I had already entered two individuals with the surname Michalski, that was Ancestry's suggestion for a name, but I changed it to remind myself that this was my Michalski DNA project.

You'll also notice on this screen that, under the tree name, Ancestry has set the default to yes for the option, "Allow others to view this tree." If you are setting up a private tree, you must deselect this option. Just click the check and it will toggle off. Then click the orange "Save" button and voila! You now have a private tree.

But...but!!!...that does not mean your tree is invisible. Not just yet. You need to take one more step: you need to make your tree unsearchable. To do this, you need to return to that Ancestry header—the home landing page where we started all this—and click "Trees," then scroll down and find the tree you just named (you remember, of course, the brilliant label you created for your experiment, right?).

Once you find your tree name, look to the far right of that entry until you locate the phrase "Manage tree." Click on that.

Once you arrive on that new page, you can see the options to change your tree name—in case you didn't like your first brilliant choice—or add a description (for whom? This is for your eyes only), or even set the home person or identify who you are in this tree. You are always welcome to revisit those possibilities later, but for now, let's get to the point: we need to make this tree unsearchable. To do that, you need to look to the header on the top of the page, the place where it says, "Tree Settings."

You'll notice that, directly underneath that phrase, "Tree Settings," there are three clickable choices. You want to head for the middle ground: the choice labeled "Privacy Settings."

When you arrive on that "Privacy Settings" page, you are now able to confirm your wish to make the tree both private and unsearchable. Step one: notice the button labeled "Public Tree." You'll see the default is already selected to make the tree public.

In order to switch this tree from its public, searchable status to its top secret status—so you can build an exploratory tree regarding your DNA matches—to make the tree private, you must scroll down to the bottom of this "Privacy Settings" page, until you find this final important detail.

By clicking on "Private Tree," you will notice the "Public Tree" green circle (above on this page) vanishes. Your tree is now private. But don't forget this important second step: to make your tree unsearchable. Look for the check box on the bottom which states, "Also prevent your tree from being found in searches." This is where you need to add your final check mark. Then, once all is done, click the orange "Save Changes" button on the bottom left, and you are finally finished.

From this point on, you are free to build your exploratory tree without worrying that you will set off a spate of incorrect copied entries in multiplied trees around the genea-universe. If you wish to share your private, unsearchable tree with a DNA match, or want to discuss your conjectures with someone else, you can always go back to the "Manage Trees" page and invite specific individuals to view your tree. And, of course, if you want to scrap this top secret mission and make the tree public—warts and all—you can always repeat this process in the reverse. Or take the nuclear option and blow up the entire tree. It's all in your control.

Once you have your private, unsearchable tree set up, keep in mind that even though you may want to start working on hints immediately, with a brand-new tree, sometimes those hints might not show up immediately. I found myself just venturing out bravely and locating my own documentation among the digitized records at Ancestry. The hints will show up eventually, once the system picks up that you are researching this surname.

One last observation: I'm not one to copy other subscribers' trees, myself, but in a stage like this, I am not beyond using the reliable work of key others to serve as trailblazer while I work on this unfamiliar family. After all, while I know a lot about the surnames and geographic locations of my own family, these DNA match families are total strangers to me; it helps to test the waters by looking at well-sourced trees of researchers who are closely related to this family. To determine that, I often look at the pedigree chart of a tree, look for the home person, and see how closely related to my target individual that home person is—and how many documents that researcher has used to support those research contentions about their close relatives.

This is definitely an experimental process, a time for research caution and much testing. In this DNA match case, where I have six different trees linked to this same, previously unknown to me, surname, there is still quite a bit of work before I see my way clear to just how each of these DNA matches are related to each other. From that point, the even larger step will be determining where my tree intersects with theirs. Likely, I'll be following a paper trail leading me back to Poland—or perhaps another Baltic state. Time will tell. I just hope it will be sooner, rather than later.

Above: All images used in this tutorial are from Ancestry.com with editorial red arrows and marks added to the original images by the author.

Saturday, June 29, 2019

Countdown to Continuing Education

It's Saturday, the very last weekend in June. In two weeks, at 8:00 a.m. Pacific Time, I'll be hunched over my computer with my finger over the "go" button, ready to register for my first choice learning opportunity at next January's week-long Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy. Granted, there are fifteen different courses to choose from, leaving the avid genealogist with far too many temptations than can be handled in one heady moment. That's why I have been lusting over this list for far too long already. I'm ready to make my decision—but I'll have to wait two more weeks.

As a logical progression to follow up on the class I chose last January—the Southern Research course with J. Mark Lowe—I am seriously eyeing the course on Virginia research. The time frame is right—from the colonial period to the Civil War—to work on several family research projects I've had to set aside. For one thing, returning to the saga of my Broyles family in South Carolina, their previous home was in Virginia, the location I'll have to address as I press back another generation. But for that pesky little matter of documentation, the back country of Virginia may well hold the key connecting another line of my family to their official designation as descendants of the Mayflower passengers. And it is the Virginia roots of another line in my family which ultimately produced the descendant whose international crime spree nearly cost him his life in an Ontario jail.

Virginia may be a location figuring prominently in the family history of many other researchers, as well—all the more reason why I want to insure my place in the registration line. There are, however, fourteen more learning options for those who don't care for the intricacies of early Virginia research. There will also be a week-long class on research in the state of Maryland—another location I'm tempted to pursue. There are courses on church records, land records, and federal records. For those pursuing their roots from other countries, there will be a course on U.S. immigration, Hispanic research, and Chinese research. And those seeking to up their research skills can avail themselves of courses in introductory DNA and advanced uses of DNA evidence, technical writing, and advanced research techniques.

That list alone is sufficient to explain my point about acting like a starved refugee set in front of a smorgasbord. I want to inhale it all—now!

Disclaimer: While I am certainly honored to be designated as an Ambassador for the Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy 2020—and have shared about their impressive offerings for several years now—this year's designation comes to me with receipt of a modest discount to the upcoming registration fee. Nevertheless, my focus is on objectively sharing what aspects of the Institute readers at A Family Tapestry would likely find helpful, and I welcome the opportunity to continue serving as eyes and ears on site during this event for the benefit of my readers.

Labels:

#SLIGExperience,

Learning Opportunities

Friday, June 28, 2019

Aunt Rose Redux

I've told this story before, but it bears revisiting while I'm on this quest to discover my paternal grandfather's roots. John T. McCann—or, as we discovered, Theodore J. Puhalski—was a man hesitant to reveal his origin. That, at least, was what my older siblings and cousins told me; I never had the opportunity to meet him, myself. Anything we discovered about our paternal roots was information which belonged to my grandfather's wife's side of the family. The only hint of a blood relationship for this man was a woman my father and his sister knew as Aunt Rose.

I have only two mementos of this Aunt Rose. One is the photograph copied below, preserved by my cousin, which included my grandmother Sophie Laskowska, my father as a young boy, my cousin's mother, and this woman whom the family called Aunt Rose. The other item is a recording made in the 1980s on the occasion of my aunt's birthday, in which my brother walked her down memory lane and captured her reminiscences on tape.

One of the stops my aunt made as she wandered among those family memories was to recall Aunt Rose. My brother gently tried to press for Rose's identity, or at least a full name, but my aunt's failing memory was able to only provide the sparsest of details. One point was that Rose was married three times. The other detail was that she had been married to a man named Kober.

As disappointing as it was to realize that that tape was the last significant opportunity to gain an understanding of the previous generation—my aunt died not long afterwards, the last in her generation—in retrospect, it wasn't hard to reconstruct the details of her Aunt Rose's life. Indeed, the first step was locating Rose's link to George Kober, from which point I could glean not only her current residence in census records, but also her previous married name (Miller) and that of her third marriage (Hassinger).

That address, as it turned out, was key to another discovery: that of Rose's mother. I had found them together as early as the 1915 New York State census, when Rose Miller was listed in the household of Anna "Krausse" on Knickerbocker Street in Brooklyn, and from that point through the 1920 census, she remained in the Kober household on 96th Street in the Queens community of Woodhaven.

Anna was there in the Kober residence, in fact, on the evening when, becoming unbearably despondent, she decided to end her own life—the event precipitating the tiny insertion in the local newspaper that alerted me to the date of her death.

If it weren't for that date, in fact, I would never have been able to obtain Anna's death certificate. The reason I couldn't find it under her name was that it wasn't filed under her name—not, at least, by the name we knew her.

This, of course, rather than solving my research quandary, only introduces more questions. Keep in mind, I had already long since sent for my grandfather's own death certificate. He had died in 1952. For mother's maiden name, someone had provided the information that she was Anna and that her maiden name was Zegar.

That, of course, would not be the first time I had discovered disagreements over names entered on death records, but I had figured it would be safe to assume Anna, Rose's mother—and, by association of Rose as my father's "aunt"—was married to someone named Krauss. Still, finding any documentation to support that was not successful—and any hope of concluding that as a tidy family arrangement was blown to bits by the name provided on Anna's own death certificate.

Why the Anna who died on the same date and at the same address as Anna Krauss would be entered under a different surname for her death certificate, I can't say, but that document now revealed that her name—at least at the point of her tragic demise—was Anna Kusharvska.

Not only was that the lone Anna who died on that date—28 September 1921—but the only one whose place of death was listed as the Kober residence. Since then, I have yet to find any other entry with that surname—or its masculine equivalent, Kusharvski. Until, that is, I began looking at the surnames in my paternally-linked DNA matches. While I haven't found any Puhalskis in those matches—nor any of its spelling variations—I did notice one thing as I looked through the Michalski trees in the Milwaukee families of my six paternal DNA matches: one of the Michalski brides had a surname with unusual spelling which kept getting mangled. While the name sometimes ended with the typical Polish -owski (or the female version, -owska, for those who knew the Polish naming custom), the name was just as likely to have an "r" inserted where the "w" should have been. Add to that the fact that "w" was often pronounced as a "v" and you have a combination rendering the same tongue-twisting ending as I found in the revelation about Anna's surname, Kusharvska.

Could that have been a regional variation? A phonetic twist only fluently rolling off Polish tongues, but not American ones? I couldn't help myself: the thought was tempting. I had to keep exploring what new details could be found since I last revisited this research problem four years ago. A lot has been added to the digitized records available online. My hope is that there may be enough new material to grant me a break-through, between these little clues and the trees of my newfound DNA matches.

Perhaps this is the perfect opportunity for me to learn a little bit more about Polish phonics.

Above: Photograph of "Aunt Rose" (top left), Sophie Laskowska McCann (top right) and Sophie's children (left to right), Anna Mae and Valentine. The photograph was likely taken before Rose married George Kober in 1915; photograph in private collection of family.

Labels:

DNA Testing,

Kober,

Krauss,

Kusharvski,

Laskowski,

McCann,

New York,

Poland,

Puchalski/Puhalski

Thursday, June 27, 2019

Race to the Finish Line

Now that I have a target surname to work on, thanks to the few DNA matches which seem to align with my mystery paternal grandfather Theodore Puhalski's roots, the next step is to do what some researchers call a "quick and dirty" tree. To do that, I'm using the tree-building tools through my subscription at Ancestry.com. It's a private tree I'm creating, of course, owing to the fact that I could very well be making mistakes as I build that tree as rapidly as possible. And one more detail: I made that tree unsearchable, lest some hapless neophyte stumble upon my work and assume it represents the gospel truth about the Michalski family in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. I certainly wouldn't want to see my error-prone experiment replicated.

At current count—and this is only after about eight hours' work—my little Michalski tree is up to seventy six names. It only stretches back three generations at this point, starting from the woman who likely was mother to one of my DNA matches and grandmother to another match, and reaching back to that woman's paternal grandfather. As I've done in the past with my maternal tree for matches on my mother's line, I've done the same for this Michalski tree: extended the descendant lines for each of the siblings in each generation, which is what provided those seventy six names. Keep in mind, this was apparently a good Catholic family with several children for each generational iteration, so it's kept me quite busy.

The catch, though, is working into this tree the Michalski lines I spotted in the other four DNA matches. Those lines aren't necessarily an extension of the one line I've been working on so far. At some point—I keep expecting to stumble upon this juncture soon, but like the carrot tied to a stick, it keeps stretching on before me, no matter how far I reach for it—I expect the other matches will belong to a brother's line of the one I'm working on now. That, however, would be the easy explanation—and a good reason why I'm keeping my eye on those collateral lines for each generation.

In the process, I'm not just looking at the Michalski surnames. I try my best to include the maiden names of the spouses, just in case. That policy may bear fruit, as I just noticed what may be a case of siblings marrying siblings.

The second reason I'm including that practice of paying close attention to the maiden names of the Michalski wives is that those two maiden names I've already spotted seem vaguely familiar—as in sounding closely like a surname I stumbled upon, back in New York when I tried every which way to ferret out clues about my mystery grandfather.

Remember the stories about my father's Aunt Rose? If you have been reading along here at A Family Tapestry for a few years, you may remember my mentioning that lady with the outlandish hat. I still can't decide whether she was a real blood relative, or just the good family friend to whom the adults in my father's life accorded the respect of the endearing term, "aunt."

A while back, I followed Aunt Rose's story as far as I could, using genealogical research techniques, and stumbled upon an unfortunate situation she experienced which led me to some documents providing a bit more identification of her family. The record I sent for included a surname so unusual, I couldn't locate it anywhere else, even in the vast humanity that populates a city the size of New York.

I am wondering now whether that original document may have contained a typo, or at least a mild case of disinformation. We'll revisit that story, beginning tomorrow, and see whether there is any hook to connect with some surnames I've uncovered in the trees of these DNA matches. It may all be a premature conjecture on my part, but I'm sure you can understand that I'm chomping at the bit and hoping to race toward the answer. I know: patience, patience! Yet all the while, my mind is wanting to rush to the finish line.

Labels:

DNA Testing,

Michalski,

Poland,

Puchalski/Puhalski,

Wisconsin

Wednesday, June 26, 2019

Tentative Tree Building

I'm not an adoptee, but sometimes the challenges I face in trying to uncover anything about my paternal grandfather seem much like the struggles experienced by children of closed adoptions. This week, I learned the hard way that I need to pay attention to the prime advice genetic genealogists pass along to adoptees. In particular, when finding a promising match, step one should always, always, always be to screencap the match's tree.

Not one to be burned twice, upon that discovery, I immediately launched that effort to save a screen shot of each paternal-side DNA match's tree. Of course, there weren't many of them, even considering I've tested at all five major DNA companies. I saved six of those trees, labeling them thoroughly and filing them away in my DNA note folder for Puhalski.

Something I noticed in the process of that exercise: one particular surname kept surfacing, no matter how close or distant the match. Of course, in each tree, it was obvious that the family had Polish roots—no surprise here for the granddaughter of Theodore J. Puhalski—and that, unlike my grandfather's arrival in New York City, each of those families immigrated to Milwaukee, Wisconsin. But I was surprised to see one particular surname pop up in each tree. Despite my thousands of matches on my maternal side, I've never had such an experience; I usually look at all those names and wonder, who are these people? None of those surnames seem to ring a bell. This time, though, is different.

Much like I imagine adoptees feel when they can tell they are getting close to their answer, it was a surreal experience sifting through this data. Once I isolated the surname I thought would be the right one to pursue, I set up a private, unsearchable tree on Ancestry.com. Beginning with the names of the deceased parents of one of my closest matches, I laid down the two entries Ancestry requires to establish a new tree, and started building from there.

I opened up the pedigree chart for each of five other matches, noted the details on the person having the same surname, and began connecting the dots. It will take a few more hours' work to connect each of the individuals with that specific surname, but I have already moved back three generations to the immigrant couple.

In the meantime, I've also encountered my first snares—for instance, one woman who has what may turn out to be a cousin with the same name and birth year. As this family is as foreign to me as total strangers, I have no clue whether my document choices are pointing me in the right direction, or whether I'll take a wrong turn, beguiled by the same name from the wrong family.

Even at this early stage, I know one thing for sure: based on its appearance in the trees of several of my DNA matches, the surname I need to follow from this point out is Michalski from Milwaukee.

Labels:

DNA Testing,

Michalski,

Poland,

Puchalski/Puhalski,

Wisconsin

Tuesday, June 25, 2019

Why Wisconsin?

It seems a bit far afield to look for relatives of my paternal grandfather in Wisconsin, when he landed—and stayed—in New York City. But if Theodore J. Puhalski was truly the orphan he claimed he was, who's to say his distant relatives didn't head to another part of the continent?

Still, it made sense for immigrants to cluster in communities, and a place like New York was just the kind of location that would seem beneficial to a Polish immigrant. Not far from the port of arrival, with lots of job opportunities and, best of all, other people who spoke the same language, shared the same customs and ate the same favorite foods, New York would be that choice. And, checking the numbers, even today, with over two hundred thousand residents claiming Polish descent—2.7% of the city's population—New York City ranks number one in the nation.

That isn't to say, though, that no other place has a large Polish-American community. In fact, ranked fourth in that same listing, after Chicago and Philadelphia, is the Wisconsin city of Milwaukee. Even more so, if the list is enlarged to include "communities" having at least thirty percent of their population claiming Polish descent, Wisconsin figures prominently in that collection.

So why would a researcher like me be surprised to see a number of DNA matches—ones which don't connect to my maternal line at all, and not even to my paternal grandmother's line—lead me away from New York and towards a place I've never even visited? After all, Wisconsin ends up having the largest number of communities boasting a significant Polish-American population of all the states in the country. And Milwaukee sits right in the middle of all that Polishness.

Then, too, Polish immigration in Wisconsin happened primarily before 1890 and from areas of Poland ruled by Germans. Milwaukee, especially, received Polish immigrants from the German-controlled regions of Posen, Silesia, and the Baltic coast area called Pomerania by the Germans. With my Laskowski roots originating in Posen and my ethnicity reports giving a substantial nod to the Baltic states, this news certainly catches my eye.

Having never previously done any research in Wisconsin—and certainly not in Poland—I have a lot of reading to catch up on. For the first stop, a brief overview of Wisconsin immigration and Polish emigration are in order from the FamilySearch wiki, as well as an overview of the history of Polish people in the United States.

There is, however, another task which needs to be done quickly, something which I discovered with alarm as I double-checked the trees of my DNA matches on this paternal side: sometimes, people decide to change the status of their tree from public to private. And wouldn't you know it: the key example I had leading back to a possible connection with my paternal grandfather has evidently converted to a private tree. It's time to send a pretty-please-with-a-cherry-on-top letter to a match I have yet to contact.

Labels:

DNA Testing,

Poland,

Puchalski/Puhalski,

Wisconsin

Monday, June 24, 2019

First Sightings

In seeking an ancestor who is leading the researcher on a merry chase, my initial tendency is to look at where we can first find him. In the case of my paternal grandfather, that is not so easily done. His first appearance was in the 1905 New York State census in the borough of New York City known as Brooklyn. At that point, he just happened to be living in the household of his father-in-law, an only slightly less aggravating ancestor to research.

There he was, although listed under a surname spelled Puhalaski and—why stop at one error?—re-entered under the "corrected" given name of Thomas. Still, the inclusion of his wife, Sophie, and his four month old son—that would be my father—helped tip the scales in our favor when combined with the Anton Laskowski household.

Jumping forward to the 1910 federal census would allay any concerns about those household listings—Theodore, then listed correctly, was still in the Laskowski household in Brooklyn, along with his wife Sophie and, by then, their two children, just as I've always known the family constellation to be. But the point of today's exploration is to see how far back in time I can go and still find any listing of Mister Mystery, Theodore Puhalski. Answer: not far, as it turns out.

If, instead of looking ahead to the 1910 census from that 1905 state census vantage point, we worked backwards in time, we could find my paternal grandmother's family alright, but no sign of Theodore. After all, he and Sophie were supposedly married in 1904, although I have yet to find any marriage record for the couple, despite diligent hand-cranking through microfilmed records of New York City marriages (yep, including every one of the boroughs, just in case).

There was another twist I needed to learn about, just to locate Sophie Laskowska's census entry for 1900, however. That was the fact that the family experimented with shortening their surname to sound less "foreign"—something I only learned when looking up my grandmother's obituary, where her younger brother Michael was listed under that shortened version. The entry for the entire Laskowski family in the 1900 census was under the surname Lasko.

Going back before that point, the only other census in which I could find the Laskowski family was in the New York State enumeration of 1892—thankfully! Before then, the 1880 census would have done me no good; the Laskowskis did not arrive in New York until after that point.

But where was Theodore Puhalski? The Laskowskis had other young men staying with them in the 1905 and 1892 enumerations, but even looking over the entire page where their household was entered, I saw no sign of any family with a surname spelled either Puhalski or Puchalski, the two variants I've already found.

It might have been a stretch, but I even recalled that early photos of my father and his family included one with a woman called "Aunt Rose." On my grandfather's death certificate—a document deserving a wary eye in attempts to use it as a genealogical guide—his mother's maiden name was given as Anna Krouse. I did discover there was a woman named Rose whose mother had that very name (although spelled Krauss), but you know I've already attempted every research contortion I could conjure up, without any results.

And so, the best I've been left with is the earliest mention of Theodore Puhalski's name in the 1905 New York State census record, when he was said to have been an alien of twenty nine years of age. With no discoverable marriage record, no appearance in earlier census records, no passenger records providing his date of arrival on American shores (despite his declaration on his naturalization papers giving a date), the man was basically swallowed up in history.

...until. Until a few DNA matches showed up which didn't seem to connect with my Laskowski side. They seemed to have something in common—all, for instance, arising from an immigrant who arrived not in New York but in Wisconsin, of all places. With no paper trail to follow into the past from my grandfather's life story, perhaps this would be the way to learn just who the man really was, and where he came from.

Labels:

Brooklyn NY,

Krauss,

Laskowski,

New York,

Puchalski/Puhalski

Sunday, June 23, 2019

What is it we Want, Anyhow?

The realm of genealogy has been an incrementally-changing universe for decades. Perhaps those microscopic changes, repeated so many times we lose count, have made the process of change invisible to our own eyes. But we have been changing.

Considering genealogy is a pursuit of history—micro-history, I grant you—it is surprising to realize we haven't done such a good job of keeping track of our own timeline. By that, I don't mean the history of each of us as individuals, but the chronology and narrative of how we've changed as an entity, as a movement.

Some of us who are not new to this ancestor chase can remember back before genealogy was a pursuit of (mostly) digitized records—before there was a Find My Past or a MyHeritage or even an Ancestry.com. Some of us can remember when the only significant record FamilySearch offered online was a transcript of the 1880 census.

Sharing was a big part of that genealogy community. Some of us can remember posting our tree on Rootsweb when Rootsweb wasn't the foundling child kindly taken in by Ancestry.com. We remember posting queries on Genealogy.com. Or GenForum. Or listserv systems hosted by universities. Or writing out our query and mailing it far away to our ancestral home state's genealogy society, to be inserted in their newsletter or journal along with countless other pleas for research help.

It wasn't that we'd crawl around on the floor, just to demonstrate that we were so desperate to find our elusive ancestors. But some of us did that, nonetheless; it was how we pulled out the drawer of the card catalog containing the call number for the archival records we were seeking, or the library book we needed to check. Sometimes, that stuff was on the bottom of the stack, and the only way to get there was to literally get down on the floor.

Even though genealogy has traditionally been a solitary pursuit, we have always found ways to connect while working on our separate tasks. We founded local genealogical societies. Created periodical publications. Started classes—which eventually grew into conferences and institutes. There has always been something about being able to talk about our favorite subject—the thrill of the chase—and know that our audience is right there with us. They know exactly what we're going through.

Now, though, it is so much easier to do our solitary research duties from the seclusion of our own personal hideouts. Do we not miss the collegiality of comparing notes and sharing stories of research conquests? Is it sufficient to simply tweet about it? Are Facebook groups adequate substitutes for discussion groups? Do Google Hangouts really replace getting together in real life?

Ever since the formation of the first virtual genealogical society, the concept of a virtual conference format was not far behind. In fact, the North Carolina Genealogical Society already offered one for 2019. And an enterprising business has dedicated their efforts to launching a series of four-speaker "eConferences"—and combining those offerings with a way for local societies to "host" and thus share in the fund-raising benefits, without the onus of doing all the grunt work of an on-site event.

The only problem is: I don't go to conferences simply to learn. It is true: we can certainly learn online as much as we can by attending an event in person—and, unlike live events, if we want to step out to the kitchen to fix ourselves a snack, or forgot we were supposed to call that business before they closed at five o'clock, we can just mute the proceedings and multi-task. We can even do it all in our pajamas, sloshing our hot chocolate precipitously near the computer screen, while not spending a penny on air fare or hotel rooms.

But I can do that stuff all the time. What I want in a conference is something special—something different than what I can get at home, listening to canned broadcasts and repeated material. I go to a conference to engage with people, to meet someone new, to hear how someone else tackled that brick wall problem. It's not the same "meeting" people through the window of technology. People tuning in to an online event are there to listen to the speaker, not the other attendees.

Perhaps conference-goers are a dying breed. But if the need to get together and communicate, face to face, is withering on the vine, then why are gathering places like coffee shops so popular? Do we want to talk to other like-minded people, or don't we? Is there room for a happy medium? More so, is there a need for a happy medium? Can in-person meetings, at least in the genealogy world, find a second life?

Saturday, June 22, 2019

Being Shortsighted About 2020?

According to the steering committee for my favorite genealogical conference, there will be no 2020. Just scratch that one off the family history events calendar.

That bombshell arrived in my email inbox only days after I left the hotel hosting the Southern California Genealogical Society's Jamboree on June second, the last day of their 50th Birthday Bash.

Barely two weeks later—from June 15 through June 17—and 375 miles to the north, the apparently successful International German Genealogy Conference opened its doors in northern California to over one thousand eager attendees from all over the United States plus a number of other countries. I couldn't help but wonder how many people might have attended the 50th iteration of Jamboree in southern California, had it not been for the magnetic pull of the biennial event held this month, coincidentally, in the very same state.

We won't be able to tell whether Jamboree attendance will bounce back next year, though, because the SCGS leadership has decided—as they positively worded it—"to take a leap forward and reinvent."

While that may sound like a noble resolution—and I commend SCGS for continuing to be the cutting-edge organization they are known to be—this has not been the first time conference organizers have gotten hints that life-as-we-know-it in the genealogical conference world may never be the same again. Agreed, as SCGS put it, "many enjoy" such alternate training outlets as online webinars, but there still is a very necessary place for gathering together to share what we are doing. You know, "Connect. Belong." Perhaps we've forgotten that lesson. Too soon.

Next year, the competition of a bright-shiny once-every-two-years-but-never-in-the-same-place-twice alternate will have vanished, only to return (thankfully, somewhere else) at the precise time Jamboree will be fired up again. Meanwhile, some regulars may have decided to look for another learning stop along the way each May or June, or substitute another event for their used-to-be regular highlight following Memorial Day weekend.

Since I've returned home, I'm already having people ask me about "that conference" I attended this month. Members of our local genealogical society are interested in being first-time attendees next year; after all, now three of their board members have been attending Jamboree each year, and always bring back a good report. It all sounds like such a great event, and they were thinking it might be for them. This would be a great time to start planning for next year's trip...except now it isn't happening.

The alternate, for those of us who believe in continued learning—especially in the networking-rich environment of face-to-face encounters—all happens, by the way, to center on those other parts of the country which involve half a day's flight, at the very least. California-centered learning for the home chickens is a very attractive choice for the wing-weary among us. Let someone else put in the bucks for those frequent flier miles for a change—that, at least, is the way I feel about it after realizing that most major genealogical conferences are held far, far from my home turf.

So I mourn the decision by the board of a wonderful regional genealogical society. True, they are asking for input from members and (I presume) attendees, but that is mainly to survey people about what they'd like to see for an event in 2021. Not 2020. That moment has already been lost, at least in the world of event planning.

What does an organization do in the face of such financial and attendance pressures? Is it just that we've all been aced out by the talking heads conjured up on our laptops? Or have there been incremental changes—bit by bit, reflected over many more than just one year's statistics—that need to be heeded, as well? Perhaps our learning styles—and our go-to-meeting desires—have morphed over the years, while that meeting style has not changed, essentially, in the last decade (if not longer).

Unless we all are willing to come together and talk about it, we may find our last, best moment to snatch such in-person events from the brink of oblivion may vanish. If SCGS is to reinvent Jamboree, it likely won't completely be reinvented without the input of many others—others willing to share what would make an in-person conference sparkle for them, once again.

Labels:

Conferences,

Genealogical Organizations

Friday, June 21, 2019

The Problem(s) With Polish Research

The trouble with trying to glean the truth from a tight-lipped grandfather—who delighted in playing the enigmatic immigrant to his grandchildren—is that one never knew what, exactly, the real story was. Even discovering—years after his passing when those grandchildren were having children of their own—that his real name wasn't John T. McCann, but Theodore J. Puchalski, we still couldn't be sure we had finally arrived at the truth.

Besides that, where did he come from? That sense of not being sure what to believe can be a persistent tormentor of those wanting to know about their family history. Census records lumped him in with my grandmother and her parents, as well, when it reported their Polish heritage by whatever national designation was the politically correct label of the day. But when I try to find any mention of that Puchalski—or Puhalski—surname in the records for the region around tiny Żerków, the origin of my Laskowski family, I come up with zero search results. Yeah, my grandfather's name might have really been Theodore J. Puchalski, but where did the Puchalskis come from?

It all comes down to one problem with this Polish research. It isn't so much the location. Certainly not the spelling—despite Poland being the home of a language far different than English, that Polish surname issue will all straighten up in the end with a large grain of phonetic forgiveness. What is really at the core of my research woes is much deeper than that. Just like what I discovered as I delved deeper into my mother's southern roots with the Broyles family story, to really understand a family's history, you need to dig deeper into the broader history of that local region. And I know absolutely nothing about the woes of the former Prussian state.

Singular among those stories I've heard of researchers stumped by their Polish ancestors is this one detail I'm experiencing: this strange need of our Polish ancestors to keep one's personal story hidden from others. Why the big secret? If I didn't know any better, such secrecy would tempt me to wonder what crimes—or, who knows, maybe real skeletons—I might find in the proverbial closet.

That's when I need to take hold of myself and realize there might be external reasons for such behavior. I need to consider the time period in which that massive immigration voyage was taken, and what circumstances the immigrant might have left behind. The age of the immigrating young man might line up with explanations in the homeland, such as strict military service laws, devastating wars, or other circumstances. Then, too, the enforced invasiveness of a government into the private lives of its subjects could not only instigate a man's plans to flee the country, but a lifelong habit of keeping close at hand any personal details which might be used against him.

While I might not be experiencing these stressors as an American woman in 2019, what my grandfather might have been living through in the 1870s and 1880s most certainly influenced his future behavior. But I can't know those details until I take the time to learn what was going on in the time and at the place he once called home.

Just like I've taken to reading the books—and their footnotes—about the local history of Pendleton and Anderson County for background on my mother's Broyles ancestors, I'm launching out into the deep of background information on the Poland of the nineteenth century. But in learning more about the Poland of my paternal grandfather's origin, I discover there really is more than just one problem. Not only is it a matter of learning the foreign history of my grandfather's early years, but it is a matter of discerning which ethnic group was his among a number of different groups lumped into the German Empire which contained Prussia. Nor is it "simply" adding that; there are issues of language and all the limits to accessibility in books, documents, records, and even online resources that come with that key to understanding we call language. Google Translate may be a wonderful tool, but it still renders a stilted version of what is really being communicated on those Polish websites—if we even can find them from our non-Polish vantage point.

With all that said, there are resources in the English-speaking world for those with Polish roots, and I certainly intend to take advantage of them. First off is the Polish Genealogical Society of America on whose website, scrolling to the bottom, I discovered the free offering of their monthly publication, "Genealogy Notebook." Then, too, I've heard good things about the Foundation for East European Family History Studies, and their annual conference in Salt Lake City in August. Besides that, there is the Canadian organization, East European Genealogical Society, which not only has meetings in its home city of Winnipeg—don't forget my research to-do list includes some work in that Canadian city, as well—but includes a Facebook page. There are more than ample resources to help me get up to speed with my background studies on the heritage I never realized I had.

Thursday, June 20, 2019

Reinventing Yourself, Immigrant Style

I've heard it said that those stories about ancestors' names being "changed at Ellis Island" are, for the most part, incorrect. I'm willing to buy that assertion, but only if I can offer a substitution: that some immigrants did indeed change their name at some point after arriving on American shores. While some of those changes were done through legal channels—I've shared about discovering my godmother's name change following her move to New York—others were likely less formal. Like really less formal.

Of course, that doesn't preclude the possibility that an immigrant did go through proper channels and that I just couldn't find the record. My grandfather's situation may turn out to be exactly that type of example. For now, though, I'm left with three simple clues—not quite the stuff that sound proof arguments are made of. I found those three clues in a census record, a draft record, and a petition for citizenship.

Mind you, not all those documents were concerning the same name. That's the trouble: it's only my opinion that they represent the same person. But have patience. I can 'splain.

From the 1910 U.S. Census for Brooklyn, New York, we can find my supposed grandfather, in what I presume was his original name, Theodore J. Puhalski, living in the household of his wife's parents, Anton and Mary Laskowski. Along with the entry for his wife, Sophie, are conveniently placed the given names of my father and his sister.

The census does make mention of the year of Theodore Puhalski's arrival in this country: 1884. That—along with the fact of his occupation—is corroborated nicely with the same report in his naturalization records, signed by Theodore at the end of December, 1905.

Just as we find such crumbs of the minutiae of Theodore's life—tiny details which match between two entirely different records—we need to replicate that same process in bridging the record gap between Theodore J. Puhalski, husband of Sophie Laskowska, and John T. McCann, husband of Sophie Laskowska. For instance, despite his death certificate reporting that he was born in Brooklyn—not!—I have a record under the name Puhalski which states the man's date of birth was August 7, 1876, and a record also asserting that John T. McCann was born on August 7, 1876.

Interestingly enough, that World War I Draft Registration Card, completed on September 12, 1918, using the name John T. McCann, declared that he was a naturalized citizen, and an alien from Russian Poland. How many guys with a surname like that do you know of from Poland? And how coincidental that both men were machinists working for a printing company in Brooklyn. Maybe even the same company. Perhaps they knew each other...

Above: Heading of the naturalization record for Theodore J. Puhalski, dated December 29, 1905, from the Eastern District of New York; image courtesy Ancestry.com.

Labels:

McCann,

Naturalization Records,

New York,

Poland,

Puchalski/Puhalski

Wednesday, June 19, 2019

Jumping Ship

To get an idea of how difficult it has been to glean the history of my paternal grandfather, all one has to do is merely take a look at the many posts I've written at A Family Tapestry over the years. That was my chief complaint on the day I launched this blog, but it certainly wasn't the last time I whined about that research dilemma. I tried tackling that problem again in 2015, though that time, the terrain over that research pathway had changed quite a bit; thanks to two different people sharing notes, our family discovered that we weren't looking for a man in New York City who was Irish, but for someone with a decidedly Polish surname.

One of those people was the daughter of one of my cousins. Doing the usual kid's homework assignment of building a family tree for her class project, she had stumbled upon an alarming possibility: that my father's mother was actually from a family named Laskowski, and that her newlywed husband, living with her in her parents' household, also boasted a Polish-sounding surname. That, in fact, was abundantly clear, once online genealogy made census accessibility a matter of a few keystrokes plus the click of a mouse. But this discovery came, back when genealogy was still an endeavor requiring cranking through microfilmed records.

The other person who gifted us with a research clue—back when the way customers viewed other people's family trees, at least through Family Tree Maker, was by ordering CDs—was actually an in-law of a second cousin once removed, from that same Laskowski line of my grandmother. He must have been a very dedicated genealogist to have gone so far afield in his own research, but no matter the reason, I'm glad to have received what, at the time, was a surprising email.

His news: my paternal grandfather was not named John T. McCann—the name we all knew him by—but actually was a man by the name of Theodore John Puhalski. Over the years since that discovery, my siblings and cousins have scrambled to make sense of not only how that could be, but who he was and how he got here.

The stories about Theodore/John were etched in the memories of my older relatives. Being one of the youngest of his grandchildren, I never had the opportunity of knowing him personally; he died before I was even born. But I could pump those others for their remembrances of every detail about the man, which I have done over the decades.

Even so, what does a little kid remember? Yet, one day—and not so very long ago—my older sister sent out a message asking, "Does anyone remember this story?" about our grandfather. He was a man who seldom spoke about his family or background—one relative produced the rare instance of recalling that our grandfather claimed he was an orphan—so my sister's recollection of a different story about our grandfather's arrival in this country was quite unexpected. She recalled him mentioning that, since he was an orphan, he had to go to work at a young age. He ended up working on a ship, and when that ship came to call at the port of New York, he made the fateful decision to go ashore...and never return. He jumped ship and became just another one of the millions of near-anonymous immigrants who now called New York their home.

Could it be? It sure sounds like the kind of story kids would relish, given a youngster's sense of adventure coupled with the lure of mystery. But it never had any follow through, not any details that corroborated that assertion. In fact, in our online era when family secrets are crashing all around me, I've managed to unearth some documents concerning him, both before and after his name change, that mysterious moment in which he reinvented himself as an Irish immigrant.

I've pulled out those records time and again, scouring every detail for an overlooked clue—yet never finding anything new to guide me further. We'll take a look at them tomorrow, just as review before launching into what can be found through these DNA matches. The real key to answers in this search, though, may well be what can be found in those other people's family trees. That, though, will require us to work on building out the branches on some very abbreviated eastern European family trees before we can reach back far enough to find those Most Recent Common Ancestors that tie us all together.

Above: Closeup of an old photograph of the man my family always knew as John T. McCann. It turns out this man was once known as Theodore J. Puhalski, born in "Germany" in 1876, who arrived in New York City possibly as early at 1884. Photograph from private collection of family.

Labels:

McCann,

New York,

Poland,

Puchalski/Puhalski

Tuesday, June 18, 2019

Tree Hopping

When I was a kid, I was a fanatical tomboy. Tree climbing was my forte. I discovered, in my pre-teen years, that the trees in my backyard were planted close enough—or had grown sufficiently intertwined—to allow me to walk from tree to tree without ever setting foot on the ground. With some well-calculated swings and leaps, I could transport myself along simply by using the branches.

Now that I'm climbing through an entirely different kind of tree, I find myself using that nifty trick once again. Stuck with lack of trees for my DNA matches? It's time to go tree hopping. In fact, it's time to swing through the trees at several tree-hosting sites. Why stop at one? Especially considering the main roadblock in comparing DNA matches: everyone loves to discover their ethnicity report, but seldom tackles the follow-through of posting their tree on the site where they obtained their DNA results.

Oh, some people do have a tree linked to their account. Usually, it looks like this:

When faced with such impossible challenges, how are we to determine the way we are connected to our DNA matches?

Fortunately, though the trees of some of my key matches are rather enigmatic—though not usually as extreme as the example above—I have a wide variety of resources, thanks to having test results posted at all five of the major companies focused on genetic genealogy. Some of my matches do, too. While their tree may not be complete at any one of those companies, they may have a better version posted elsewhere. I certainly have followed that formula, too, preferring the tree building system at Ancestry over those at other companies.

Besides knowing to look for my matches at multiple companies, I also have learned to search for the ancestors of those promising matches at other websites. For instance, while I find the AutoClusters tool to be invaluable, I don't much take a shine to the tree building program at MyHeritage. If I look at a match's tree on that website and (understandably) find it just as weak an offering as my own shriveled tree there, I'll go hunting elsewhere for the target ancestor from my match's tree.

In the case I'm currently tackling, MyHeritage's AutoCluster tool has pointed me to one cluster which seems to represent relatives affiliated with the mystery family of my paternal grandfather's origin. Keep in mind that I know next to nothing about my grandfather; if it weren't for concerted effort by cousins and other kindly but distant relatives, I wouldn't even have known he ditched his decidedly Polish-sounding name for an Irish model, well into adulthood in New York City. So locating four DNA matches which seem to connect to that paternal line is a big deal for me.

The problem is that most of those matches are at the range of third to fourth cousin. And that line in my tree drops off precipitously at the mere level of grandfather. My matches' trees don't reach much farther. How, then, do we make any connection? After all, to find the Most Recent Common Ancestor for a third cousin requires at least knowing the details about each match's second-great grandparents.

The answer comes by seeking out other trees which extend the branch even further than our match had done. This is quite easily accomplished at Ancestry.com, especially among researchers willing to add more than just their direct line ancestors. It is among the branches of those siblings' spouses that I often find the information I'm needing on the common ancestor.

Right now, I'm trying to figure out how one branch of the Puchalski family—if that indeed was my grandfather's real name, and not just another alias he picked up—ended up in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, when my family was decidedly a bunch of New Yorkers. I'm getting several other matches at other testing companies which also resonate with that Milwaukee connection, so I know this cannot be a fluke. It's just that we all have a couple more generations to push back before we can isolate the answer to our joint family history connection.

Before we get to that point, though, it would be a good idea to start at the beginning of the story: just how I and my cousins came to discover that our family name wasn't really Irish, after all.

Labels:

DNA Testing,

New York,

Poland,

Puchalski/Puhalski,

Wisconsin

Monday, June 17, 2019

DNA:

Can't Lose Sight of the Purpose

With the avalanche of DNA matches pouring in to a test-taker's account, it's not hard to lose track of the real value of genetic genealogy. We look at those hundreds of DNA matches we've supposedly just received in our account, and cheer when we recognize, among all the names, those of familiar cousins or aunts or uncles—totally ignoring those mystery names we've never heard of. It all takes on the aura of a toddler unwrapping a Christmas package—who, amidst squeals of joy, takes more interest in the bright, shiny wrapping paper than the expensive gift just bestowed by her doting parents.

I certainly can admit to falling into that trap, myself. I'm a sucker for Bright Shiny, I confess. And being task oriented, I set to work to classify all those matches—starting with the closest, easiest targets to handle—so I could get the right names in the right family slots. Getting those DNA matches organized made me feel so efficient.

But after a long while, it dawned on me: it's the ones we don't know about who are the keys to breaking through our family history brick walls.

That insight didn't come to me freely. I had a little help. The nudge came just after this year's RootsTech, when MyHeritage launched their Theory of Family Relativity and, along with that announcement, introduced this nifty tool they dubbed AutoClusters. (If you have not yet seen this tool in action, the best explanation I've found was a session with MyHeritage's Ran Snir at Legacy Family Tree Webinars.)

I requested my AutoClusters from MyHeritage, and within a short while, received an email with a zip file including a matrix of my matches, clustering them into inter-related groups. All that was left for me was to examine the groups to see what ancestral names each cluster might have in common.

Some groups were large, while others much smaller. The large ones, predictably, were from my maternal side, where our colonial heritage has had plenty of time to percolate descendants through multiple generations. But among the smaller clusters, I spotted one which contained very few names of matches, in which all of them had one thing in common: they seemed to come from eastern European roots, but had no connection to my paternal grandmother's Laskowski line. Could they actually point me to my mystery grandfather, the orphan teenager who once used the name Puchalski or Puhalski, who supposedly arrived on American shores AWOL from his duties as a sailor on a Polish ship?

It was then that I snapped back to attention about the strength of this fun toy we dabble with in our genealogy. It's the power of this DNA that can help us isolate the disparate descendant lines of a particular ancestral root—specifically, the family line cut short which has otherwise left us without any clues.

While the tool at MyHeritage is at the disposal of their subscribers—and, I presume, those who transfer in their raw DNA data from other testing companies, as well—the AutoClusters program is not original with them. Thanks to Evert-Jan Blom, the program was first offered at Genetic Affairs. Besides the version available at MyHeritage, it is now newly accessible for Tier 1 subscribers at GEDmatch. The plus to those other versions is that the user can define the upper and lower limits to the parameters, whereas they are pre-determined at MyHeritage.

Regardless of which version you decide to use, I believe the best starting point, for me, was at MyHeritage. I am already a subscriber there, and my DNA matches there far outnumber the count at any of the other testing companies—including some family trees with very Polish-sounding surnames I've not encountered elsewhere.

Perhaps it was a good omen that the group in question for my purposes was cluster number thirteen—my aunt always claimed that was her lucky number—but regardless of the dynamics, in checking out the four people named in that one cluster, it was easy to click through and gather the details on how we all match. That, in turn, is providing my research assignment for this upcoming week: to trace those trees and see if I can construct a proposed family tree that points me to my paternal grandfather's origin.

Labels:

DNA Testing,

Poland,

Puchalski/Puhalski

Sunday, June 16, 2019

Remembering Fathers—

and Other Family Members

Happy Father's Day! If you still have a father within traveling distance, I hope you were able to take some time today to express your love and appreciation. Those of us who don't wish we could.

There is still a piece of my dad around for me to remember. Of course, I have many memories—and photographs, in case I forget. But thanks to his DNA—and his father's, too—every time I look in the mirror, I can see part of his face looking back at me. I resemble my dad. And though I never met him face to face, judging by the pictures my older relatives have been kind enough to share with me, I can see I look like my paternal grandfather, as well.

That magical secret code locked up in the genes passed to me from my paternal side may one day—soon—open up a few clues on a mystery that has long had our family stymied: just where my paternal grandfather came from. Who would have guessed, years ago, that we'd someday be all a-buzz about this thing called genetic genealogy? And yet, thanks to relatives connected to this patriline who have been willing to participate in DNA testing—especially my brother, whose test included his Y-DNA—I now have the clues to begin cracking that century-old mystery.

Between the magic of this technology—many of us are still struggling to get our heads around the science that lies at its basis—and the reports of thousands of matches showing up in my accounts at all five major testing companies, it's easy to lose sight of the power of the thing in the midst of overwhelming data. After all, I have 3,780 matches at Family Tree DNA, 1,638 at Ancestry, 1,213 at 23andMe, and 8,031 at MyHeritage. That's a lot of work attempting to track how these DNA relatives connect to my family tree.

In the past year, I had focused my family history research on my mother's line for a very specific reason: my plan to take a specific research course at the Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy. Though I am still following through on that task—in the past two weeks, I added 133 names to my mother's tree, to bring up the total there to 18,585 individuals—I am shifting my research goal for the remainder of this year to conquer the one question of just where my paternal grandfather came from.

Work on my father's tree had come to a near stand-still in the past year. Still, since January, I've added an incidental few names as interesting family tidbits came my way. Right now, that paternal tree stands at 538, the smallest of my family trees. But thanks to the appearance of one DNA match which surfaced after I used MyHeritage's AutoCluster program, I believe I've made a connection with someone who may be related to me through my paternal grandfather's line.

It's pretty much the same for my husband's father's tree: not much work in the past year, except for the occasional discovery of an obituary or other bit of news. Right now, my father-in-law's tree stands at 1,531—up eight in the past two weeks, only because I've been chipping away at a Tully connection on this tree which I can't quite yet figure out. I know—mostly from old family photographs lacking labels—that there are more Tully relatives out there; I just never could find any documentation to verify exactly what the connection was. But now that I'm looking more closely at these records, I'm finding names to add to my father-in-law's tree, after all.

So it looks like this will be the season for working on both fathers' lines—mine, and my husband's. I'll be rushing to take advantage of the Father's Day sales at some DNA companies, before the end of the weekend, as more relatives agree to participate in testing. Every little bit of help enables me to paint one more speck of that picture about a grandfather I never really knew.

Saturday, June 15, 2019

Virtually Here:

Opportunities for Learning

It's June 15. If you haven't yet thought about registering for a virtual program through the Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy—but always promised yourself you'd try it someday—you'd best start thinking, and fast. Registration, open today at 11:00 a.m. mountain time, may not fill up quite as fast as Thomas Jones' SLIG course last January—so far, he holds the SLIG record for reaching capacity in six minutes from registration opening—but just be safe and assume procrastination will not serve your purposes today.

I won't be attending the fall SLIG Virtual sessions, though I was sorely tempted. Three different courses will be offered: the All-DNA Advanced Evidence Analysis Practicum (beginning in October), Intermediate Foundations (eleven weeks, beginning September 10), and Virtual Nordic II: In-Depth Swedish and Finnish Research (also beginning in September).

While each class, team-taught by multiple instructors, sounds interesting, I've found I prefer the opportunity to do my learning in person, so I'll opt to boot up my computer and hover my finger over the "register here" button in time for the traditional January sessions, held in Salt Lake City. It's a good thing registration for that session won't begin until July 13 at 8:00 a.m. my time. (See how dedicated I am?)

After having attended several years of traditional SLIG each January—if you've been following A Family Tapestry for a while, you may have noticed my posts from previous years—I'm honored to have been selected as a SLIG Ambassador this year. Either way, I can't say enough about this learning opportunity, whether the choice is to learn in person or virtually through online connections. I guess I just love genealogical research, and finding ways to increase my skill sets is a high priority.

Right now, though, I'm torn. I have my eye on two different SLIG 2020 January sessions. Both represent a natural progression from my Southern Research class from SLIG 2019. One delves into the specifics about researching in Virginia from the colonial period through the Civil War. The other takes a close look at the big research opportunities in the little state of Maryland. Both states represent the early landing places of our family's ancestors. Thankfully, I'll have another month to ponder which choice will yield the best practical outcome for my family history research pathways in the upcoming year—but you can be sure I won't dally once the morning of July 13 arrives. Those classes can fill up lightning fast!

Disclaimer: While I am certainly honored to be newly designated as an Ambassador for the Salt Lake Institute of Genealogy 2020—and have shared about their impressive offerings for several years now—this year's designation comes to me with receipt of a modest discount to the upcoming registration fee. Nevertheless, my focus is on objectively sharing what aspects of the Institute readers at A Family Tapestry would likely find helpful, and I welcome the opportunity to continue serving as eyes and ears on site during this event.

Friday, June 14, 2019

The Privacy of Life

Searching for what turns out to be permanently missing records for either the Canadian or Irish baptisms of our Tully forebears points out one thing: how invisible people from previous generations seemed to be. With precious few documents kept that reached down to the level of the individual—tax records seeming to be the rare exception for those lucky enough to have ancestors who owned anything of value—that very fact bestowed upon such individuals the liberty to disappear from the scene, if they ever so wished. While we bemoan the lack of any indication of who Dennis Tully, husband of Margaret Hurley, might really have been, there seemed to be little question of a new arrival in any westward-expanding town who showed up, claiming to have that very name—or, perhaps, reinvented himself with an entirely fresh version of a name.

If a person were to try that same approach today—becoming a new person in a new town—there would be several impediments to such an attempt. Permission to operate a vehicle in order to drive to a new location would require a driver's license, upon which would be imprinted various details about that person's appearance, linked to a system which could enable tracking of that same specific driver, no matter where those travels led. Even worse, some governments might have already instituted other tracking devices, such as one in my home state, which would enable the "right" people to determine the location of the driver, just based on cameras which capture passing license plates on major roads—not to mention mobile phones with GPS tracking devices.

For those so concerned about their privacy that they shun any form of licensing for vehicle operation, air travel would likewise impede upon their wish to go undetected. Passports required for international travel, and photo identification for domestic air travel open the door to portability only for those willing to exchange such privileges for the momentary surrender of their privacy. And, should any weary travelers wish to lay their sweet heads down for rest, a hotel stay would likely also violate that desire for personal privacy—as would the use of a credit card to buy necessary supplies or meals during the journey.

Such a list could go on and on, of course—casting today's quest for genetic privacy in a more unrealistic light in comparison with other currently expanding realities—but it is not today's citizens whose privacy I am marveling over, but those of a previous century. Without the records to trace them back through the ages, the family history of our Denis Tully and his younger counterpart, the Dennis Tully of my husband's DNA match, will indeed remain obscured.

I'll have to concede loss—at least temporarily—in my attempt to identify just who Ontario resident Dennis Tully, born somewhere in Ireland around 1830, might have been. There are no records—at least that I can currently find—to demonstrate who his parents might have been. There may be circumstantial evidence, such as his DNA match to other known Tully descendants or clusters of similar surnames in more recent baptismal records still in existence, but until there is enough upon which to build a solid proof argument, I'll be left with endlessly continued search attempts.

Such a (temporary) defeat calls to mind another ancestor whose cloak of invisibility, granted by a less document-driven century, also enabled him to escape home and show up in another country—with a totally different name, as well. Just show up, claim a new identity, and voila! An ancestor reinvents himself. And 1800s American communities—especially the larger cities—seemed not to bat an eye. It was the anonymity of the hoi polloi.

I have such an example hiding in my own family tree: my paternal grandfather, the eastern European immigrant who somehow showed up in New York, then decided to change his identity to better match the signs of the times. No matter what the oldest members of my generation remember of him, there is simply not enough to cobble together a true identity of the man. More importantly, there isn't a shred of evidence to go by when trying to determine his origins. It was easy to slip into a country and claim one was someone one was not in an era of greater privacy. My grandfather was proof that that was possible. Even his own family didn't know his full story.

...until now, that is. Perhaps, in this era of restricted privacy—when an individual's every move can be told by a mesh of tracking devices—I'll now have the tools to figure out his origins. Perhaps. With the anomaly of one distant DNA match and some aptly-designed computer-assisted help, a pointing finger is poking through that shroud of anonymity. I may be able to crack that code of privacy, after all. Even in the face of far less documentation than our century has accustomed us to expect.

Labels:

DNA Testing,

Documentation,

Ireland,

Ontario Canada,

Tully

Thursday, June 13, 2019

Nota [Not So] Bene

A genealogist is not likely to take news of an impending brick wall easily. In fact, I've been turning every which way, examining record possibilities, struggling to escape the verdict: realizing there was no easy explanation—or convenient documentation—for the other Dennis Tully I'm now pursuing.