Charles McClellan's 1839 will may not have named every single one of his surviving children, but we can rest assured there are other ways to collect the details we seek. One of the best approaches is to study the stories of the others related to this family line for clues.

In addition to mentioning his concern for his two youngest children, Adeline and Samuel, in his will, my fourth great-grandfather Charles McClellan also spoke specifically about the relationship of the person he appointed as his executor: "my eldest son George McClellan." It was that son who was my third great-grandfather, so I have already gathered quite a bit of information on that son's life. It was the others in the family of which I knew very little—but being siblings of George, and children of Charles, these were identities I could ill afford to neglect. With that, it's time to attend to the due diligence of being nosy enough to snoop out details on their own stories.

But what were their names? Charles' will didn't provide us much guidance.

In a shift in thinking regarding searching digitized records, genealogical organizations are now seeing the value in making not only the principle party a searchable field, but all the other names mentioned in a document, as well. After all, if we follow the genealogical adage, "Start with yourself," by necessity we need to work backwards in time. Our first encounter of parents' names may likely be when their children are mentioned in an end-of-life document—especially as our research moves us farther away from the era of those handy birth and death certificates.

Unfortunately for Charles McClellan—but of extreme benefit to those of us researching his story—his name did come up in a matter of someone's end of life. I say "unfortunately" because of the many times I've heard elders say they never should live to see the death of their own children, and that is indeed what happened to Charles.

The document which may have revealed another of Charles' children's names was a Jefferson County, Florida, court report of the 1838 appointment of an estate administrator in the wake of the unexpected death of William G. T. McClellan.

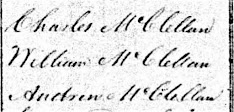

From records posted earlier in that same decade in territorial Florida, I had been able to find the name of three McClellan men, not in Jefferson County, but in nearby Hamilton County. Listed along with one Charles McClellan, in a row on the same page, were William McClellan and Andrew McClellan.

In census records of that era, of course there was no guarantee that three men with the same surname were related to each other—or even that those three McClellan men lived near each other. Relying on just one document for family history research can be a risky proposition. But placing two or more such records in sequence may help to piece together a story.

In the case of that William McClellan in the Hamilton County census for 1830, his age fell within the bracket from fifteen to nineteen years. To find a head of household listed at such a young age seemed unusual, but that was not the only detail which caught my eye in his case. In his household was only one other person: a female also within that same age range.

As it turns out, there was a story behind those 1830 tick marks: William and his wife were newlyweds.

Well, let's rephrase that. They were newlyweds if we can buy the theory that the Jefferson County clerk was, um, maybe dyslexic and the county's Justice of the Peace perfunctory to a fault. Here's how the timeline goes.

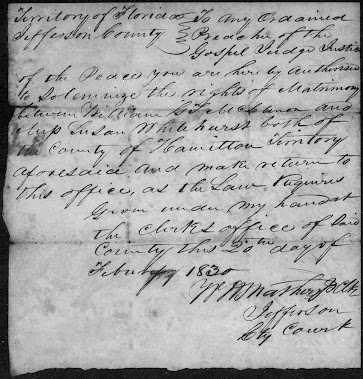

On the twentieth day of February, 1830, a young man from Hamilton County, listed as William G. T. "McClenon" made application in Jefferson County for a marriage license to wed Miss Susan Whitehurst, also from Hamilton County.

At the end of the subsequent month, the Jefferson County registers duly noted that Justice of the Peace Solomon Hall had performed the ceremony to unite said William G. T. "McClenon" and Susan Whitehurst in matrimony on March 4.

By following Susan Whitehurst McClellan through records tracing her life—she subsequently married someone sharing her maiden name—we can see that she and William had two children, a son and a daughter, before William's own untimely death.

At the point in which their tragic loss was brought to the court's attention, it is clear to see William certainly hadn't had any plans of dying; he left no will. The Jefferson County court appointed another McClellan—Henry—as administrator of William's estate, but that process came with the requirement of a bond. Standing in as security for that bond were two men, named as Charles McClellan and Charles D. McClellan, likely father and son. The document was posted in the court records on January 14, 1838, not quite eight years after his marriage to Susan Whitehurst had been recorded at the same location.

With that, we obtain clues that Henry and Charles D. McClellan might well be siblings of the unfortunate William G. T. McClellan. I say "clues" because at this point, we can only assume their involvement with William's estate was due to a familial connection. But it provides a jumping off point for us to explore these collateral lines further. After all, where these potential brothers of William—and thus, sons of Charles the elder—were born will point us to the places Charles lived before migrating to territorial Florida in the late 1820s.

Image credits: Listing of three McClellan names listed in the 1830 census for Hamilton County, territory of Florida, courtesy of Ancestry.com; authorization to perform Jefferson County, Florida, marriage courtesy FamilySearch.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment