Sometimes, genealogy research takes on an aura that some of

my D.A.R. friends might call steeping one’s tea. For others—like my husband,

the consummate grill master—the preferred analogy might be to that of

marinating a great steak. In the face of genealogical brick wall challenges, whether

you prefer to liken your research style to a reserved, tea time pace or take it

with a Chicago

steakhouse flair, you know you will have to park that need for speed.

Sometimes, you’ve got to get out of that research rat race

and wander around the data. See the sights. Smell the smells. Poke around those

facts that just don’t make any sense, and see if they’ll release any of their

secrets.

Right now, I’m stuck on determining just who this man was

who married my grand-aunt,

Mary Chevis Davis. Granted, I initially was sidelined

years ago when some kind soul in Florida mailed me a copy

of an obituary for an F. Luther Kite—with right birth date included—who turned

out to be married to someone totally different.

It didn’t help, of course, that his wife’s name in no way

lined up to the one I had on record.

It also didn’t help that the man, himself, had shown up in

records throughout the years sporting different names. Kite versus Kyte.

Luther. Franklin.

Flavius.

Flavius? Where did that

come from? The Roman Empire has been long gone.

So, I took a walk around the digital data neighborhood,

taking in all the sights I could see. Granted, it did cause me to wander a bit,

but a little research exercise never hurt anyone.

Since I had—thanks to

the 1940 census, subsequent to a

divorced Luther’s return back home to Carter County, Tennessee—a copy of

his mother’s death certificate, I spent a stretch of time getting familiar with

every line on that document.

Real

familiar.

Granted, though Maggie Kyte’s death record only provided

those blasted initials for her father’s given name, at least it gave me a

glimpse of Maggie’s maiden name, as well as her mother’s maiden name. Combining those details into search terms, I

looked for a Simmons household in Carter County, Tennessee—the place where the

family arrived after moving from their home in Virginia—that had a mother named

Mary, a daughter named Margaret, and a father with any name starting with

either a J or an F.

Though we are so spoiled now with instantaneous research

results at the click of a digital button, that became an order which could not

be filled, at least not for the 1880 census. I did, however, find a Simmons household that

included a father with the right initials and a daughter Margaret with the

right age and place of birth.

Only catch: J. F.’s wife’s name was Susanah.

While that didn’t fit the picture I was seeking, since I was

in wander mode, I took my time and checked out all the details. One of the

first things I noticed was that the oldest son in the household—a young man by

the name of Edgar—was eighteen years of age. That in itself might not seem

unusual to you; after all, the father in this household was forty four,

himself.

But his wife claimed an age of thirty.

Either Susanah was being coy about her age—you know what

they’ve always said about not asking a lady her age—or she was not the mother

of Edgar.

Coy or precocious, the woman also listed her place of birth

as Tennessee, when the entire rest of the

family was born in Virginia.

I’m thinking Susanah didn’t have that first baby at the age

of twelve. I’m thinking this was a case of a step-mother for Maggie. And isn’t

that grand, considering I’m still on the search for Maggie’s mom, Mary. I’m

ready to move on to the next document.

Not so fast—there are other details to see before jumping to

the previous census record, the first of which is the fact that Maggie’s dad’s

name didn’t quite align with the

initials given in her death record for her father’s name. Instead of J.F., this

census reversed the order.

But, hey, this is Tennessee. When it comes

to names, that can happen around there.

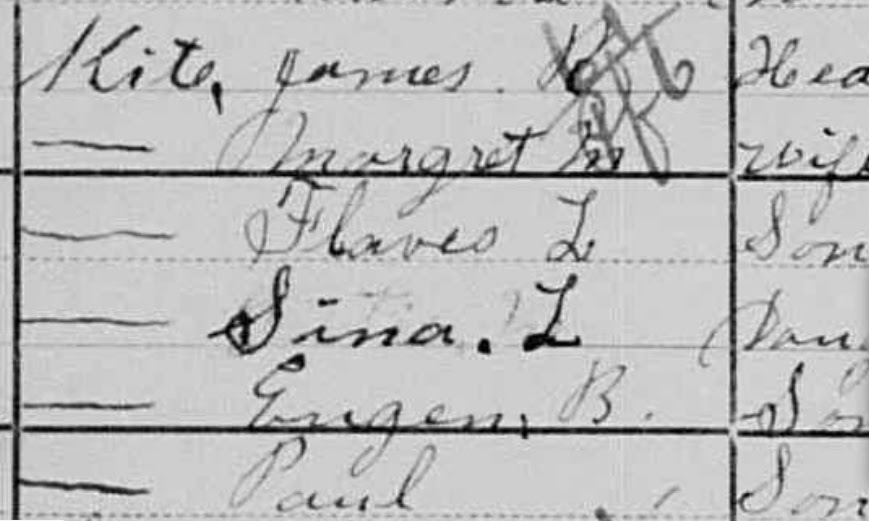

J.F. or F.J., I want you to take a look at the details in

that 1880 census record. Not only is the order of the initials reversed, but

the census taker actually provided a full first name.

You’ll love this: it was Flavious.

Granted, that’s what happened to one census record for

Maggie’s son, the younger Flavious. One census record, apparently, does not a

name make, though, for the former junior Flavious had quickly re-invented

himself as Luther, then later as Franklin,

as the decades rolled by.

So, if Luther’s maternal grandfather was identified as

Flavious in 1880, what did the record say for him in 1870?

Thankfully, a little consistency reigned in

the 1870 census,

for once again, Maggie’s dad was identified the same—this time spelled

correctly as Flavius J. Simmons. The 1870 canvasser for Carter

County must have been a Roman Empire aficionado. Or at least he knew how to

spell.

That’s not all I found by hanging around all the documents

strewn on the trail of Luther Kite. Taking the slow way around these records, I

spotted one last detail: the name of the informant on Maggie’s death record.

Do you remember

my remark about other discrepancies, over

the years, on the census records for Luther’s immediate family? In one decade,

his sister was named as Sina, while in a previous record, she was marked in as Lena. I presumed Lena

would be the correct version—but taking one more look at her mother’s death

record, I saw that, apparently, her name was Sina, after all.

By the time of Maggie’s death—

October 21, 1943—Sina was

married and signed her name to the report using both her maiden and married

surnames. Being that this was after that magic point of 1940, she spelled her

maiden name as Kyte rather than as Kite. And she indicated her married name was

Blitch.

There was one more bit of trivia about her entry there. For

address, Mrs. Sina Kyte Blitch indicated she lived in Jacksonville, Florida.

Now, you may not find it at all significant that Luther’s

sister had moved that far away from her home in northeast Tennessee. But I do. You see, the obituary I

had found for the

possible rest of

the story about F. Luther Kite indicated that he had died in Duval County, Florida.

In a city named Jacksonville.

By the time he had

died in 1973, his former wife Chevis had been long gone,

having succumbed to cancer in 1942, so it would be quite possible that

he had remarried.

There was something, however, about all the unexplained name

changes and spelling changes that cautioned me to doubt that finding. In the

end, I tossed the obituary, not even entering it into my records.

Now that I take the time to think it all over, I’m not so sure that was the right thing to do.