My March research goal: learn something—anything—further about my fourth great-grandfather, Charles McClellan. It was relatively easy to see that the man died in territorial Florida about 1839; we have his will filed in Jefferson County.

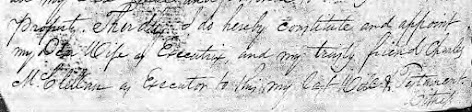

That, however, was a discovery which brought with it problems, foremost of which was that the man's overarching concern for his two minor children obliterated any felt need to mention the names of the rest of his family. Now, we know him only as Charles, father of Samuel and Adeline. Oh, and father of George, since Charles appointed his "eldest son" to be his executor.

What about the others? Looking at the lines of other McClellan men in the region, mentioned in each other's various legal documents, I can see their names appearing in tandem from time to time, but that doesn't assure me that they were truly brothers.

Take, for instance, the 1830 census for nearby Hamilton County, Florida. In that record, as we've already discussed, there were three listings for McClellan heads of households: Charles, William, and Andrew. Charles, we've already explored, and likewise William. But what about Andrew?

Finding these names mentioned in more than one northern Florida county bothered me. What if the young Andrew showing up in the Hamilton County census record in 1830 wasn't the only Andrew McClellan in existence in the region? I had to check out the possibilities. But looking at the three counties in which I've found at least some of those McClellan men—in Hamilton, Madison, and Jefferson counties—I couldn't spot more than one Andrew McClellan.

Let's see what we can find on this third McClellan man listed in that 1830 census record. For one thing, his was one of the smallest of households, containing one man between the ages of twenty and twenty nine, and one woman somewhere between the ages of fifteen and nineteen. Newlyweds? According to one local history book, Andrew McClellan married Christianna Watts in Hamilton County on December 10, 1829, a matter of months before the 1830 census was taken—but that will be a document retrieved during an in-person visit, as it doesn't show in any online resources I've checked.

And yet, by 1840, there was no sign of this young Andrew McClellan in Hamilton County. By the time of that later census, though, there was someone by that name and approximate age heading a family of six in nearby Columbia County.

Looking at land records for Andrew McClellan, one can begin to sense my concern that there was more than one man by that name in the region. The search results at the online source for the General Land Office Records of the Bureau of Land Management showed no land acquired by Andrew McClellan in either Hamilton County or Jefferson County where the other McClellans had lived, but in Madison County and Suwannee County.

Of those land acquisitions, the Madison County ones were earlier transactions in 1835 and 1837. And yet, in 1840, the only Andrew McClellan listed in the census in northern Florida was living in Columbia County, not Madison. Then, from 1844 through 1848, there were further land transactions, this time listed in Suwannee County.

But wait! Suwannee wasn't established as a county until 1858. How could it be listed as the location of a land transaction occurring in 1848?

Likewise, the earlier records started to make me question the listings. Notice that Jefferson, Madison, and Hamilton had their beginnings in the same year: 1827. Could a land record from the 1830s have gotten the geographic designation wrong? Perhaps it is time to dig a little deeper into the interface between how records were recorded at the Bureau of Land Management as compared to the county formation in territorial Florida. Perhaps there was lag time, or even an attempt to identify the land's location by the subsequent geographic description.

As for Andrew McClellan showing up in the 1850 census in Columbia County, I can cheer that the names of his household members were individually identified—and sigh from the relief of realizing that wherever he lived in Columbia County, it was likely the same piece of land which, with the county boundary change in 1858, became the newly-formed Suwannee County. From that point, we can follow Andrew and Christianna through each decade—with the exception of the missing entry for the post-war 1870 census—and find them still in Suwannee County.

That, incidentally, was the same county in which another McClellan lived: George, the son of Charles named as his executor, back in his 1839 will. The only other document I can find Andrew linked with any of the other McClellan men we've been researching concerned that mutual struggle experienced by all northern Florida settlers, the series of battles called the Indian Wars. In that time period, we can find an application for a military headstone for Andrew McClellan in which, following the many handwritten notes affixed to the official document, it is clear that someone was having trouble locating any record of Andrew's service.

On the back of the application, someone wrote in the comment, "2nd Lt," and identified Andrew's service with "Capt George E. McLelland's Co."

Seeing that inscription brings up a point—likely the same difficulty which not only faces us as we explore this McClellan family, but also was encountered by the record keepers tasked with confirming Andrew's service in the first place. In researching this line, I've seen that surname represented as McClellan, McClelland, McLellan, and McLelland. Sometimes, the initial "c" is substituted by an apostrophe: M'Clellan. Or the "Mc" handled as a prefix, or entirely optional to include at all. Can they all be representing the same name?

Whether Andrew served in 1836 in George McClellan's company as friend, neighbor, or family is hard to tell from the few documents available to me at this point. Because Andrew's 1880 passing was far beyond the dates of the other McClellans' deaths, there is no expectation to find their names affixed as witnesses or even executor of his will—though the reverse may be true for other McClellan men who predeceased him. More searching to come before we exhaust that point.

That Andrew had a long life, though, presents its advantages. He lived past the point at which census enumerations switched to name all individuals in a household, and even to the point of listing relationships between members of a household. Andrew and Christianna were still around for the 1880 census, living in their married daughter Mary's home, providing not only a link to the next generation, but an indicator that I had missed this daughter entirely in previous enumerations.

That type of entanglement I can welcome with open arms. That is the way we are able to knit family lines together over the generations. That, in fact, brings me back to that original will—the one in which Charles McClellan was so emphatic about the care of his two youngest children. After his passing, what became of Samuel and Adeline? Perhaps following their story will help weave this family together in ways we haven't yet discovered.

Above image from the Application for Headstone or Marker for military veterans, application made on October 2, 1956, on behalf of Andrew McClellan (1810-1880); image courtesy Ancestry.com.

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)

.JPG)