The old saw about genealogy researchers never being

satisfied until they go back just one more generation may come to mind with my

comments today. I hope you will find this instance excusable. While

documentation for the 1843 Ohio

birth of Joseph E. Flowers would suffice to qualify for membership in the Ohio Genealogical Society’s “Settlers and Builders of Ohio,” I’m not satisfied to

settle for that designation. I believe it will be possible to demonstrate that

Joseph’s father was himself in the state of Ohio before 1821. It is that December 31,

1820, cut-off date that is my target to qualify my husband and his family as

descendants of the First Families of Ohio.

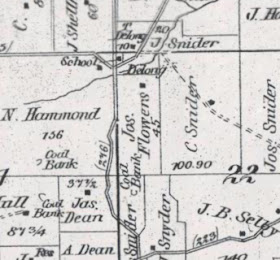

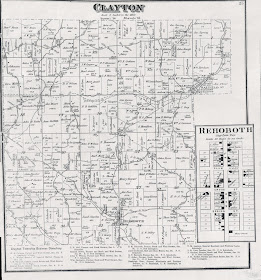

Let’s take a look at this target ancestor. Joseph E. Flowers’

father was Simon T. Flowers. Just a few years before Joseph was born, Simon

married one of the young women from the area’s extensive Gordon family—Nancy Anna Gordon, daughter of James and Sarah Rinehart Gordon, who had arrived in Perry County

from Pennsylvania

in the early 1830s.

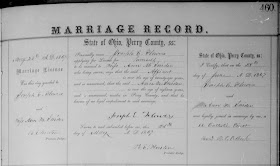

The old Saint Joseph

Church in Somerset,

Ohio, was the site of the exchange of Simon

and Nancy’s

vows on June 24, 1840. In the following twenty two years, they raised at least

thirteen children. Their son Joseph was the oldest of the five sons.

Joseph’s father, Simon, was himself from a large family. I’ve

already explained my dilemma regarding Simon’s place of birth—listed in some records as Pennsylvania, in the midst of brothers both older and younger

having been documented as born in Ohio.

The main offending document is Simon’s death record. The

index to the Record of Deaths, Perry

County shows Simon’s place of birth as Pennsylvania, while aggravatingly,

the line below his on this index page belongs to his older cousin Susannah, who

was born in Madison Township of what was yet to become Perry County, Ohio. (From this link to a scanned copy of the “F”

entries, page forward through the alphabetization until you reach the Flowers

entries.)

And yet, the 1850 census shows a “do” or ditto mark for

Simon’s place of birth, under the preceding line’s “O” for Ohio. The legend takes up the “Pa” for the

subsequent line, correctly indicating his wife’s origin in the state of Pennsylvania, then

switches again to “O” for their firstborn daughter.

Though the 1860 census spells his name “Simeon” instead of

Simon, following the quote marks signifying “ditto” up the line to the previous

state indication, it once again shows an “O” for Ohio. Again, for his wife, the legend

reverts to “Pa,” then to “O” again for the children.

In 1870, the census pattern holds steady. In a clear, legible hand,

the entire word “Ohio” is boldly inscribed,

correctly shifting to the fully-written “Pennsylvania”

for Simon’s wife, and back to “Ohio”

for the children remaining at home.

In 1870, the census pattern holds steady. In a clear, legible hand,

the entire word “Ohio” is boldly inscribed,

correctly shifting to the fully-written “Pennsylvania”

for Simon’s wife, and back to “Ohio”

for the children remaining at home.

What most likely were three different census-takers

reporting on documents spaced ten years apart seem to be in harmony about one

conclusion: Simon Flowers was born in Ohio,

not Pennsylvania.

Why then the discrepancy for his final document? Perhaps

whichever family member reported to the itinerant census takers did not become

the one responsible for providing the information for Simon’s death record.

Perhaps it was Simon himself reporting all those years—well, at least up until 1875.

As to who completed the information for Simon’s death

record, there is no way now to determine this. While later death certificates

in some states indicated the name of the informant providing the details, this

was not the case for Simon’s 1875 passing. Ohio law initially required the keeping of

death records in 1856, but with lack of universal compliance, the state passed

a second law requiring each county’s Probate Court to keep these records. This

is why Simon’s death is recorded in an index held by the Probate Court

of Perry

County.

The index, as you can see, held very little information. Of

those few facts, the information could have been provided by one of the adult

sons—perhaps even Joseph, himself—or it could have been inserted by a kindly

distant relative wishing to help the family during this time of burden. It

could even have been one of Simon’s wife’s Pennsylvania-raised Gordon family

members.

So this leaves me with the score of three to one. Three

census records affirm birth in Ohio, one death

record insists it was really Pennsylvania.

What now? Taking a close look at the Ohio Genealogical

Society’s Lineage Society Rules and Application Procedure file, it appears that

census records are acceptable. Does that mean the story’s over? Perhaps it is

just me who is uncomfortable with the ambiguity. I think I just want to find a

little something else to fill in the blanks in my own mind.