We started this journey through the tales of the Flannigan

family of the Upper Peninsula in Michigan

via a chance find of a newspaper clipping in a grandmother’s personal papers.

The trail began with a Chicago

priest, Father Patrick Michael Flannigan, whose will named three siblings:

Richard, John and Agatha.

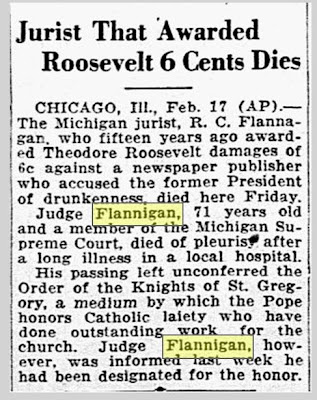

We’ve already met Richard—well-known in the region due to

his professional connections. We’ve gotten to know Agatha as best we could,

owing to the fact that she lived a good portion of her life in the household of

her brother Richard.

But before we move on to John, let’s take a look at that

list of siblings once again—mainly because we now have two mentions of nieces

for which puzzle pieces seem to be missing.

Rewinding the data to about 1870, and returning to Greenland, the original homestead for the Flannigan

family since the late 1850s, let’s first look at the census record.

Besides the father, James, and the mother, Ellen, the

children in the 1870 census ranged in ages from seventeen to nine. Admittedly,

these names don’t line up with what was showing in the 1860 census, but let’s

take a tally of where we are now. With each one born in Michigan, we see the sons as William, Mathew,

Edward, and Richard. The two daughters are Margaret and Mary (whom I am

presuming is the one who turned out to be Mary Agatha).

At this point—1870—Richard and his two sisters are enrolled

in school. All the others are listed as laborers.

Conveniently coinciding with this record, and helping us to

hone in on the date of the Flannigan family’s move from Greenland in Ontonagon County

to the city of Marquette,

is this 1873 city directory.

Even with the inevitable misspelling of the surname, we can

see our family grouping all given with the address as “Washington near 6th.”

The father,

James, is listed as an engineer.

William,

now about twenty, is a machinist.

Mathew, a

nineteen-year-old, serves as printer.

Edward,

listed as “Ed.” at seventeen, is a carpenter.

Richard,

the youngest at fifteen, is a weighter—though most certainly still also attending

school

Yet, from the earlier 1860 census, we see there were also

sons Thomas, John and James. Could the James in the city directory actually be

the entry for the son, rather than the father? And could either of those other “Flanigan”

listings at different addresses actually belong to this family’s own John? And

what has become of Thomas?

Of the sons listed in the 1873 directory, we find that three

of them are no longer alive by the end of the decade. Mathew, the printer, dies

of typhoid fever as a single man on November 16, 1875 in Marquette. Barely a month later, and now

listed as a carpenter, his unmarried brother William is accidentally shot and

dies on December 19. And in 1879, the same year as his mother’s passing, Edward

the carpenter exits life on August 6 from the same ailment that eventually

precipitates his mother’s demise in November. Of the sons listed in that 1870

census, the only one remaining by the time of the 1880 census is Richard.

What of the others—the ones who left home before the 1870

census? Of the sons for whom we have names, Thomas and James have left no

discernible paper trail—most likely cleverly camouflaged by creative spelling

tactics. John—the one son we can vouch for—has moved to Colorado. And Patrick, by the end of that

decade, is ordained a priest and headed to Chicago. Of the others making up the unnamed

list of James and Ellen’s reported “ten sons” we have no clue.

But there were daughters—besides Agatha, a Catherine and a

Margaret. And later, there were nieces reported—Katie Cook and Mrs. William Crago—that

will help hone our search parameters.

Until those hidden trails reveal some clear direction,

though, our next focus will be yet another Flannigan to head to Colorado: John.