Thursday, February 27, 2020

When That Name Keeps Showing Up

Today, there are quite a few unanswered questions about Simon Rinehart, the man who was my mother-in-law's third great-grandfather. Though we know he was likely born in southwestern Pennsylvania about 1774, we don't know who his parents were, and thus have no idea of any possible siblings, either.

Not only that, but the only details we do know about him are that he had a wife (or perhaps two) named Ann, and children named Sarah, Jesse, Hannah, Lucinda, and Charlotte. With those children's dates of birth spread over twenty three years and the family's travels spanning three states—Pennsylvania, Kentucky (where Sarah was born in 1795), and Ohio (where Sarah and her husband, James Gordon, settled, along with the rest of her father's family)—you would think a record somewhere would answer more of my genealogically-oriented questions.

Not.

I won't rehearse all the attempts I've already made on this puzzle; if you're curious, you can read the posts tagged Rinehart from the last couple weeks' work. There is, however, one last-ditch attempt to be considered: to look at the will of Simon Rinehart, which was presented to the probate judge in Perry County, Ohio, on March 8, 1853.

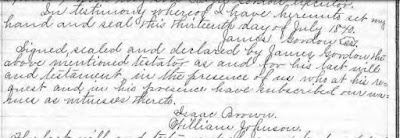

This is the will which, frustratingly, neglected to actually name Simon Rinehart's "beloved wife." The will was brief, consisting of three directives, plus the usual legal terminology. Signed by the testator's mark, as he couldn't sign his own name, it gave the name of the two witnesses as Peter Long and Matthew Brown.

The interesting point about this will, though, was that Simon named not one but two executors. One, of course, was his only son, Jesse, who at the time of his father's death would have been about forty six years of age. Despite Jesse's mature age, his father deemed it best to appoint a second executor, a man named Isaac Brown.

Now, if you recall, there has been no mention of a surname like Brown in all the wanderings I've made through the Rinehart family history, as well as that of the two possible maiden names for Simon's wife Ann. And yet, we know by experience that those names which appear for executors—and even witnesses—are not pulled out of thin air. Very few men trawled the neighborhood—or queried the guys hanging out, for example, down at the local pub—to see who might be up for executor duties, come reckoning day. Most men named in an ancestor's will were chosen for a specific reason, and that reason oftentimes was a family tie.

What was curious about one of the names presented in Simon Rinehart's 1853 will was that I thought it was vaguely familiar. Though it wasn't a name I recalled seeing in my mother-in-law's family tree, I did remember seeing a name like that in another recent will I had reviewed. I went back to look, retracing my research steps until I found it: the name of a witness to the 1840 will of Simon Rinehart's son-in-law, James Gordon.

The Gordon name, you might recall, had been one of those surnames showing up first in the colony of Maryland, then moving to Tenmile Country in southwest Pennsylvania about the time of the Revolutionary War, and, finally, on to Perry County, Ohio, by the early 1830s. Though Simon Rinehart's oldest daughter Sarah was born in Kentucky, her family had moved back to Greene County, Pennsylvania before the birth of her brother Jesse in 1806, thus situating Sarah to meet James Gordon and marry him there by the end of 1819.

Sarah and James Gordon had a large family, with seven of their children born in Pennsylvania before their move to Ohio by 1832. Though their eldest son, Bazil, had barely reached the age of majority before James passed away in 1840, James appointed him to be executor of the Gordon estate, along with Sarah as executrix. However, that document also included the names of two witnesses, one of which was, as I suspected, Isaac Brown.

Whether the two documents identify the same person when they name this Isaac Brown, I can't yet tell—though given that the dates of the two testaments were only thirteen years apart, it is quite possible they both refer to the same man.

The trouble is: we are now researching a man by the surname of Brown. While, agreed, we are not talking Smith or Jones, we are still challenging ourselves to identify who this Isaac Brown of Perry County, Ohio, might have been—furthermore, to see if we can figure out why both James Gordon and his father-in-law might have called upon this Isaac Brown to interject himself into the most personal of their financial affairs. That is a question which may take some time to unravel.

Above two insets are excerpts from, first, the 1853 will of Simon Rinehart of Perry County, Ohio, and second, the 1840 will of James Gordon, also of Perry County; images courtesy FamilySearch.org, free to access, following completion of sign-in for permission to log on.

Labels:

Brown,

Gordon,

Greene County PA,

Kentucky,

Perry County OH,

Rinehart,

Wills

Subscribe to:

Post Comments (Atom)

Could it be too much to hope for? Could Isaac unlock some clues?

ReplyDeleteI've learned to stick with that premise that no name is included in legal documents without a significant reason. Here's hoping that significant reason turns out to be significant for us!

Delete