When I was a kid—you know, those early years when I knew I

was “born wanting to do genealogy”—I asked my dad where he came from. Like,

where his parents were born. And their parents.

His answer—as I’ve often mentioned—was “Aaah, you don’t

wanna know that.”

My mother, always ready to fill in the blanks, recited the

party line for me, possibly in hopes of placating me and making this genealogy

stuff all go away: my dad’s father was Irish and his mother was German.

End of story.

Of course, I didn’t stop trying. But I wised up to other

ways to find these things. I learned about research. Paper trails. Census

records. Newspapers.

Alas, all these things were only accessible to those willing to travel to the appropriate source, and in many cases,

considering my age and stage in life, this was not possible.

And so, the story languished. Until.

Until changes happened in the family. For one thing, I left

home and moved across the continent to attend college. People grew up. Attitudes

changed. Possibilities opened up.

And people died.

One of my cousins—actually, a cousin once removed—was tasked

with the inevitable “Family Tree” homework assignment at school. About that

time, I had headed south to L.A.

on some business and ended up visited my brother. We got to talking about that

mysterious family tree—he being quite a bit older than I, and me thinking

perhaps he would remember stuff from the relatives he knew from his childhood.

He mentioned the upshot of our cousin’s homework assignment.

“We might be Polish,” he said with marked incredulity. Being Irish was a big

thing for my brother.

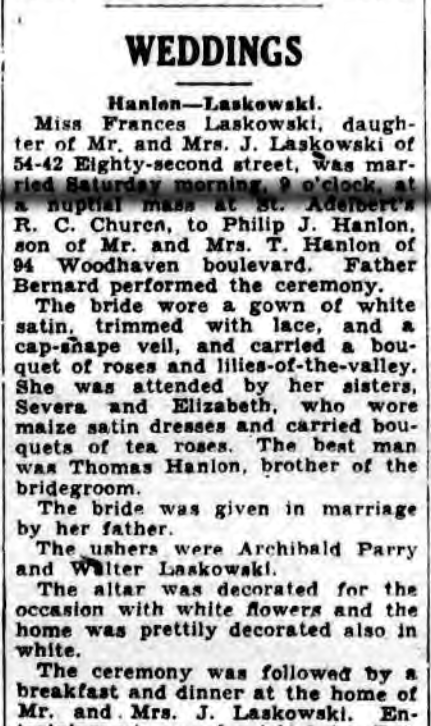

It was in that conversation that I first heard the surname

Laskowski. Before that, I had had no idea. My brother floated a few more

possibilities—some that yielded results, some that turned out to be bum leads.

A bit later—perhaps, mindful of our conversation about

family roots—my brother flew back east to attend a gala event thrown in honor

of my aunt’s seventieth birthday. He managed to bring a tape recorder with him,

and sweet-talked my aunt into letting him interview her as the guest of honor.

She obliged.

During the interview, he deftly led her back down memory

lane—mostly about special times in her own life. But then, he slipped in some

prompts about remembering other family members. My aunt talked about her

favorite cousin—the same Francis Laskowski whose wedding was eclipsed by my

aunt’s own—and some of the times they shared together. When her memory seemed

to falter, my brother would gently prompt her for descriptions and names. Nicknames.

Married names. Details about relatives, drawn out oh so gently.

Tenderly, he walked her back down that memory lane until she

was talking about the previous generation. And then, unexpectedly, my aunt

mentioned that her father had a sister.

The tendency to grab at details of this kind can be

overwhelming when you know absolutely nothing about a family’s background. But

an over-eager reaction can breach the mood—and in an instant, the interview can

be aborted.

My brother tried to coax more information from his

reminiscing subject. She was able to remember that this woman was married more

than once. Thankfully, she remembered one of the married names, but the other

one slipped her mind. It was simply not there to recall.

It was such a gift to receive a copy of that taped interview—not

only because of all the treasures of family history it contained, but because

within the decade, my aunt, herself, passed away, taking all those memories

with her. Even though I was subsequently able to return back east to visit with

her once, before her passing, I could tell her memory was fading. In

conversation, she would confuse people’s identity. By then, it would have been

unlikely that her recollections would be reliable.

Shortly after this time was when most of our family entered

the computer age. Instead of letters, phone calls, or those infrequent

transcontinental visits, we could connect by email or chat. I started to

compare notes with some of those cousins-once-removed (the virtue of being the

child of someone so removed in age from me is that my contemporaries in family

circles were all the children of my

cousins—handily equipping me to have no difficulties whatsoever grasping those

once-removed labels that cause so many such confusion).

Two of these cousins were daughters of a woman who had died

early, as a result of cancer. They had been going through their mother’s—my

cousin’s—papers after her passing. They noticed some unusual documents, which

brought an odd episode to mind. Once, her daughter had caught her with some

music of the Polish national anthem or other patriotic music from Poland. It had

been hidden away in the piano bench—never taken out when others were present. When

questioned, the woman wanted to change the subject and even began shaking. Why?

What was there to cover up?

My cousins now think that this was one way their mother was

attempting to connect with her roots. Somehow forbidden to do so as a child,

she couldn’t deny the pull of that basic question: who am I and where did I

come from?

Other stories came out—about my father and his sister being

strictly told never to reveal their roots. This would result in awkward

scenarios for this younger generation. My aunt could never, for instance,

invite her high school friends home with her, after school, for fear they would

realize her mother had to speak to her grandmother in a foreign language.

The story that got told to family was that the switch of

names was to allow their father to get a job. There was much prejudice against

the Poles at the time, but favor was turning toward the Irish—so the story

went. How a Polish immigrant was able to pass himself off as an Irish-American,

I’ll never know. I would think the accent would get in the way of such a ruse.

At that time, I had not yet discovered the paternal surname,

Puhalski. But even when I did learn of that possibility, it did not permit me

to gain any traction in furthering my research.

Oh, you can be sure I tried—I poked, I prodded, I massaged

the data gleaned from governmental documents, but without any success at

discovering the identity of this paternal grandfather.

But…he had a sister? Perhaps this was my key to bypass this

genealogical enigma. I could start a new research trail: finding out about Aunt

Rose.