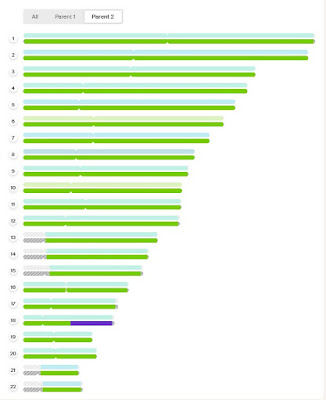

Sticking out like a sore thumb on my husband's recent Ancestry DNA chromosome painter display for "Parent Two" (his father) is a solitary section of chromosome eighteen. Unlike the other twenty one autosomes, which were uniformly festooned in green for my father-in-law's Irish heritage, a significant portion of this one lone chromosome was painted in a royal blue.

Think "Prince of Wales" on this one, if you are wondering about that royal blue. Not that we are related, of course, but just for a few neighboring centiMorgans, my Irish-extraction father-in-law can claim a Welsh heritage. How can that be?

I am wondering whether it is owing to that family history scoundrel, John Stevens, my husband's second great-grandfather, who may or may not have used his real name when landing in midwestern America. After all, who'd be there to check? Life in 1850s Indiana did not include drivers' licenses, nor any type of photo identification, for that matter. Birth certificates were unheard of, and upon his arrival in a new land, who would be there in Lafayette to vouch for his existence?

As we saw yesterday, Stevens is what is called a patronymic surname. In other words, "son of Steven"—or, more to the point, "Steven's son." Just drop the "son"—which sometimes didn't happen in the few records I have been able to find after his arrival in America—and you're left with Stevens.

When I think of surnames in that fashion, they usually turn my attention to the Welsh, for whom such surnames are not unusual. Of course, Welsh surnames have their own idiosyncratic traditions, perhaps owing to their long history. But the hallmark that stands out the most to me—at least, after fixed surnames were adopted in Wales in the fifteenth century—is that many of them take the form of a given name with a letter "s" added to the end. Think: Steven + "s" = Stevens.

Could the reason I haven't been able to find John Stevens be due to his native land being Wales rather than the County Mayo he claimed was his origin? Why would someone report his homeland incorrectly?

In the case of British subjects of the 1800s, there might be compelling reasons. Impressment into service, especially into the British navy, was a practice upheld by Parliament in laws passed up to 1835, though in practice was not widespread after the Napoleonic wars.

Ireland, however, was another story. British subjects themselves, the Irish saw heavy recruitment by the Royal Navy, including impressment, even up through 1922. But what if John Stevens wasn't Irish, after all?

Another possible offshoot of this missing man situation could have been the case of desertion. Though pay arrangements were such that it was to a man's disadvantage to abandon his post, desertions from the British navy were not uncommon, providing yet another reason for disguising one's identity.

These, however, are all possibilities floating in my mind as I wonder about John Stevens' choice of migration route—from the north of Ireland to the southernmost American port of the time, New Orleans. Could it really have been John Stevens who traveled that unnecessary distance? Or was there a valid reason for him to have made such a trip?

Then again, was the man's name really John Stevens at the onset of his adventure?

No comments:

Post a Comment