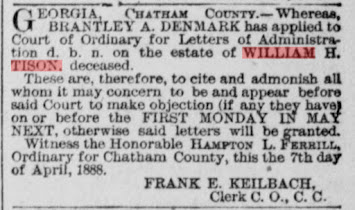

Are government documents always correct? I've read, from time to time, rants by genealogists who seem to think our official record keepers are not above reproach. Death certificates often are the prime exhibit—which certainly makes sense, considering the reported names for parents of the deceased are blurted out by their grief-stricken survivors at some most inconvenient times, all in the name of the minutiae of bureaucracy.

There are, however, less excusable record gaffs. I'm convinced census enumerators should fall within this category of, um, less-sainted scribes. An inconvenient discovery in the midst of my quest to discover Catherine Laws' parents' names will be today's prime exhibit.

Over the weekend, I continued combing through my twenty five DNA matches whose trees contain the surname Laws, and my five DNA matches linked through Ancestry's Thru-Lines readout. I had already hypothesized that Catherine Laws, my second great-grandmother, could claim as her parents a couple from North Carolina who had settled in Greene County, Tennessee, after Catherine's marriage to Thomas Davis in nearby Washington County. That most likely couple, William and Elizabeth Laws, had headed a household in Yancey County, North Carolina, in 1850 which included a daughter named Catherine, of an age close to that of my Catherine.

Examining my DNA matches, I had found two small candidates whose trees showed them descended from Catherine's (as yet theoretical) brother, Pine Dexter Laws. One of those was a match sharing a precariously tiny twelve centiMorgans with me, whose paper trail I confirmed led to a relationship of fourth cousin once removed. The other supposed descendant of Pine Dexter Laws shared an even smaller genetic match with me, topped off with an assumption showing in the paper trail which was not adequately supported by documentation. For Pine Dexter and his DNA descendants, let's say we're at the fifty-fifty mark.

Another DNA match, this time descending from Catherine's possible brother Larkin Laws, turned out to be from a line of descent from which I had encountered problems with the first match I had studied: a daughter whose records indicated a given name different from that asserted by the DNA match. Though the match shared a slightly stronger total—twenty three centiMorgans—I am not comfortable using that to bolster my contention about possible parents' identity yet.

Matches linked to a third Laws descendant, Elizabeth, presented an uncomfortable consideration for me as well. Besides the small centiMorgan level, those matches' trees included a different given name for their "Elizabeth"—especially in marriage records—while I find no marriage record at all.

And yet, there was that other Laws descendant whose DNA results I stumbled upon, no thanks to the tools at Ancestry. Sharing thirty seven centiMorgans, this was another descendant from Pine Dexter Laws—an unmistakable name and identity—leading me back to that specific line of William and Elizabeth Laws. How could I doubt such a clear marker?

To complicate matters—and doesn't a solid proof argument require us to not ignore those "inconvenient" discoveries?—in a surprise moment of realizing that even Catherine herself, after her marriage, had lived briefly in Greene County near her family, I realized another possible genealogical train wreck headed down my research track.

Sure enough, Catherine Laws and her husband Thomas Davis were recorded in the 1870 census in the neighborhood—and on the same census page—as the household of her supposed father, William Laws, and one page ahead of the mangled entry for her brother, Larkin Laws.

There was only one problem for that entry regarding William Laws.

While his age was close to what I had seen previously—a birth about 1804 instead of 1802—and his shoemaker occupation was certainly spot on, this North Carolina man's unmarried daughter Elizabeth was suddenly twenty eight, when she should have been ten years older. But that wasn't the problem that concerned me.

Then, too, the twelve year old William in the household could well have been the elder William's grandson—and son of Larkin from the first marriage I had mused about last week. So I wasn't too concerned about that discrepancy, either.

The main problem about this Laws household in the 1870 census was that it contained an entry for a woman named Catherine Laws. As in, the same name as my second great-grandmother, the one I was presuming was represented by the entry three households later in that same 1870 census page. If Catherine Davis was William Laws' daughter, who was this other Catherine in his household?

This, of course, made me backtrack to my original problem-solving exploration of 1850 census possibilities. Could it be that William Laws was not the correct identity for Catherine's father? Should I have examined the alternate possibility, that of the Stokes County, North Carolina, household of John and Jane Laws?

Going back to that alternate possibility, I rolled that scenario ahead a few years to check for confirmation. As it turns out, John and Jane did have a daughter Catherine as well, but you will undoubtedly understand my relief to discover that their Catherine was married in her home county—ironically, in the same year as my Catherine, 1856—to a man named Elijah Frye.

Thus, at this point at the end of my research month, I can safely discard that Catherine's parents, John and Jane Laws, as the correct answer to my research question. And while I'm not yet thoroughly convinced of the solidness of the alternate option, I can concede that some of the DNA matches pointing to William and Elizabeth Laws have validity.

Above all, I can hold tight to my conviction that not all government documents are created equal. And remember to find more—many more—paths to documentation confirmation.