For those whose family trees are riddled with cases of "Endogamy Lite," the challenge becomes to identify those ancestors whose names appear in more than one spot on the pedigree chart, so that they can be "merged" into one ancestral profile. This is most easily achieved by those who use a desktop-resident database management program, such as Family Tree Maker, where the program can list the possible duplicates for you at your command. On Ancestry.com, the process is a little different, though still very possible. It just takes a couple more steps.

Since Ancestry.com is my primary go-to workspace for researching and cataloging my family's trees, I generally manage the entire process from that service. Once I realize—as I discussed yesterday—that I've just entered a new profile for an ancestor with a strangely familiar name, I go searching to see whether I can confirm that hunch.

First, on my tree's main page (showing the pedigree chart) or from any ancestor's profile page, I click the down arrow on the bar on the top left, just under the Ancestry tool bar, listing the name of my family tree. From there, I can select the option, "Tree Overview."

That leads to a page with categories of information on the current status of my tree. The part I am interested in right now, in order to find duplicates, is to look at the listing for all the individuals included in my tree. For that, on the "Tree Overview" page, I look to the far right column, down from the listings "Home Person" and "Last Person Viewed" to find the heading "Summary." From there, I select the clickable link labeled "People," which brings me to a new screen.

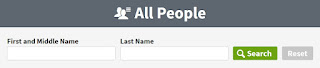

On this new page, "All People," you can enter any name from your family tree, and the Ancestry program will bring you to that person's profile page. That, however, is not my purpose for visiting this spot today; I want to look over an alphabetically arranged list of all the ancestors in this tree, to scan for duplicate names.

Keep in mind, since this tree contains over twenty five thousand profiles, I'm going to want to hone my search to a more manageable level. Since I already know my mother-in-law's portion of this family tree contains many duplicate entries—remember that "Endogamy Lite" situation—my approach, when I've already made a mental note about such details, will be to enter the surnames I feel are most likely to contain duplicates.

This is the tree for which there are many possibilities. But I don't want to simply scan for duplicate names. Everything can conspire against me if I use such an approach—everything from father to son name-afters, to multiple cousins named after a favorite ancestor. I have to widen my visual inspection to more than just names.

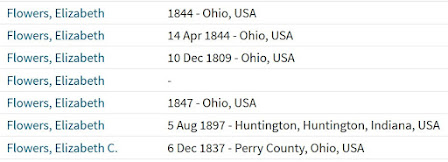

For instance, my mother-in-law's tree overview can contain multiple listings such as this:

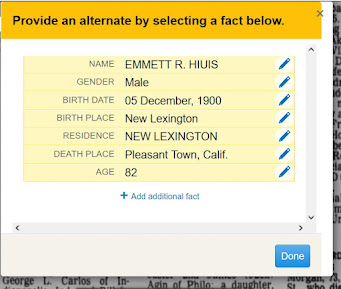

Which ones are duplicates? I can't really tell unless I also keep an eye on the rest of the details included in the tree overview readout. This tells a more complete picture:

In this case, I can more clearly spot the fact that the first two listings might represent a repeated entry, one which requires me to take a closer look before I decide to merge the two profiles. In addition, this process helps me realize the Elizabeth without any further details entered could also possibly represent a duplicate—but that I'd first need to do further comparisons with that individual before deciding how to proceed.

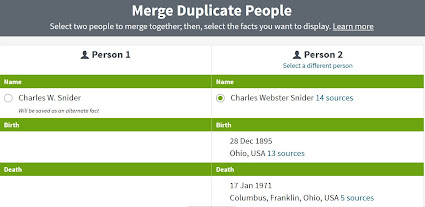

And so I continue, working my way through the specific surnames which I already know are most likely to yield duplicate entries due to ancestral families intermarrying. After that Ohio Flowers family sweep, I move on to another surname with such possibilities, Snider (also spelled Snyder in some branches), and visually check the names in the alpha listing. I run across another instance similar to my question about the Elizabeth with no further details: a Charles W. Snider versus a Charles Webster Snider. Could those two entries represent the same person?

Often, when building a family tree from the present—for instance, starting with the home person as self, spouse, or our own parent—we have no way to foresee that any one ancestor in the family line will eventually claim more than one spot in the bigger picture. In an oft-intermarried family history such as this one, I might be researching the ancestry of another surname, and end up with one ancestor marrying a Snider. Or I might have entered the parents' names for the spouse—a habit I try to maintain to better identify those who have married into the line of the branch I'm researching—and have nothing else with which to identify the person, other than name.

In the case of the man named Charles Webster Snider, it turns out that he was my mother-in-law's second cousin once removed, a man who had a daughter he named Mary Ann. This Mary Ann was born in 1929, and eventually married a man named William James Kelly.

Turning to the other entry, the one for Charles W. Snider, I see from his nearly-empty profile page at Ancestry.com that he also had a daughter named Mary Ann. While I have no entry for this Charles' wife as I do for Charles Webster Snider, the coinciding names for the daughters seem compelling. Looking further, I see that not only did Charles W. Snider turn out to be a duplicate entry for Charles Wesley Snider—arrived at in this family tree from different research directions—but that I had already been working on merging yet another duplicate for this identity, as well.

All that is left to do, once I've double checked documentation to confirm the double entries, is to merge the two individuals—a process we'll discuss tomorrow.