Years ago, when I would tell pen-pals or other foreign acquaintances that I live in California, I would invariably get this response: "Oh, you live in California? You must go to Disneyland every day!"

Not quite. For me, that would involve a six-hour drive...one way. Not, incidentally, including L.A. traffic.

I know that, but my correspondent from Greece, or South Africa, or even Australia might not have that figured out. Even friends from small American states like Connecticut or Rhode Island can't seem to comprehend the need to travel hours on end, just to reach a destination in the same state.

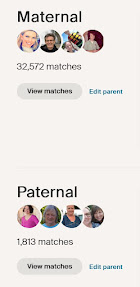

Now that I'm exploring the DNA matches I've found from Poland on MyHeritage, I'm becoming painfully aware that my ignorance of my matches' geography may cause me to fall into the same trap: thinking each DNA cousin lives down the street from those matches we share in common, when in fact, their distance from each other's home may reveal another kind of distance.

I say that because I already have discovered how distance in that home country translated into very distinct branches of my ancestry, even though they all came from what is now the same place: Poland. Keep in mind, these branches on my family tree represent ancestors living well over one hundred years ago. Life in Poland at that time was very different. Unlike our current opportunities to travel quickly over great distances, giving not much thought to the expense or logistics, a much more impoverished country of that time did not support such conveniences. Thus, communities were far more insulated from each other.

For my research focus this month, I already know the region from which my Laskowski ancestors emigrated was part of the Prussian empire once called Posen. That is where I've been most successful at finding documents confirming their relationship to other family members. Of course, any of their descendants still remaining in Poland are not guaranteed to still be living in that same tiny village of Żerków. But I feel fairly confident that those descendants may still be living nearby—yet, how would I know if I didn't have even a rudimentary knowledge of the territory?

Much like my country is distinguished by regions—mountains, plains, valleys—and political divisions like states and counties, other countries have their own systems to classify these areas. Especially in questions of where to look for records, it helps to understand the system in place in our ancestor's native land. We can glean even more about political relationship, occupations and ways of life, by delving into these non-genealogical concepts. In a way, it guides us in how to read between the lines on those dull, boring vital records.

The first thing I realized about researching Poland, of course, was the war-torn geographic and political upheaval experienced throughout the centuries. Poland was not always Poland. In the case of some partitions, the Poles were beholden to control by other countries' governments, making an imprint on those from whom we are descended. We need to understand this.

Then there are the words we see often, prompting us to wonder whether we should inquire further about them. One of those words, for me, was voivodeship. Finally, I had to look that word up. Apparently, the word is used in many eastern European countries to designate an area administered by a voivode. Seems logical enough...but what is a voivode? Think of that as a governor. Or a duke. Possibly a military commander. Use of the term stretches far back in history.

In Poland, we can think of a voivodeship as a province. It represents the highest level administrative division of the country. Though we can orient ourselves to that concept, unfortunately the labels and location borders have changed over the years—in the latest case, quite recently (1999). And yet, I still find it helpful to wrap myself around the notion of overlaying current geographic and political divisions on top of the historic ones. I want to know where, in today's terms, my ancestors once lived. And I want to explore the "personality" and qualities of each Polish region—which, in snapshot form, we can do, thanks to material readily available through the Internet.

I discover, in my exploration, that while we might think of Poland as for the "Polish," even that country has ethnic variations. I first learned that when I discovered the Kashubians living in the region of historic Pomerania where my Polish paternal grandfather's family originated. A simple data overview—like this fact check regarding Poland—can help orient the researcher to variations within a country, and lead us away from painting our ancestors' history with too broad a brushstroke.

It is said that one of the largest diasporas in the world is that of Polish immigrants. Of that estimated twenty million people of Polish descent living in multiple countries around the world, nine million live in the United States—almost three percent of the population.

While there are several pockets of American population still celebrating Polish festivals and customs, and baking traditional Polish dishes, I suspect a great number of them don't completely grasp the full breadth of the experience of living back in Poland—let alone the Poland of a century removed from us. In my attempts to connect with my DNA cousins still living in Poland, at the least, I can prepare by augmenting my understanding of the territory, the life experiences, and the people whose ancestors may have been neighbors of mine.

.jpg)