When struggling to research a mystery ancestor, the one problem with utilizing the "F.A.N. Club" method is that it can be prone to luring us down rabbit trails.

You know me and rabbit trails: I'm game to give anything a try. Who knows whether the path will turn out to be a trailblazer leading me to discover a key unlocking the mystery.

My rabbit trail today began innocently enough: an Ancestry.com subscriber sent me a message. Like many messages I receive, this one contained just enough detail to get me curious, but not enough to provide me the tools I need to give an answer.

Since I maintain many more than one family tree on Ancestry, I couldn't at first even determine which tree my correspondent referred to. The writer mentioned she was doing research on behalf of another family member, and had discovered that a certain person in one of my trees was cousin to the great-grandmother of the relative she was helping.

As it turned out, that person was in my mother-in-law's Perry County, Ohio, family line—a scramble of intermarried surnames, cross-connected from generations back. Not a specific ancestor on my mother-in-law's direct line, the person in question was married to someone in her collateral line.

I looked at the surname involved—Elder—and realized I owed myself some work on that line. In fact, that person's grandfather was a Perry County settler who had been born in Maryland, not unlike the Schneider line I've been working on this month. Feeling that reminder about "birds of a feather" flocking together, just as I had on Tuesday, I wondered again about that helpful F.A.N. Club concept: the fact that our ancestors often made decisions about life in relation to the community they've grown close to. Family, business and social associates and neighbors made a significant impact on our ancestors' decisions—including their decision to pick up and move to a strange new location far, far away.

This is where today's rabbit trail journey began. I picked up the trail with Teresa Elder, mother-in-law of the individual mentioned in that message I received. Teresa was born about 1838 in Ohio, likely spending her entire life in Perry County. Her father, though, was from Maryland. What was his story? Could he have also come from the same place as our Nicholas Schneider?

It never hurts to look, I always tell myself, and dove in to James Elder's story. Though he was in Ohio by 1828—witness his marriage to Mary Lynch in January of that year—James was born in Maryland. Despite having a birth year estimated to be in 1800, James Elder was flagged as a hint by Ancestry for the 1800 census. While I know that surely, such an entry would be for a head of household, not a newly-arrived infant, I couldn't help myself: I took a look.

Sure enough, there was an entry in the 1800 census in Maryland for someone named James Elder. Unsurprisingly, that was the name of the head of household for a family comprised of five sons and one daughter. What was most interesting, though, was the residence listed for this family: Emmitsburg, same place where we had found the Schneider family before their move to Perry County.

If there was one other Perry County family in Emmitsburg, could there have been more? I scoured the pages of names listed in that 1800 census and discovered several households with another familiar surname: Flautt.

What I haven't yet mentioned about the Schneider family—soon to become known as the Snider family in Perry County—was that in subsequent generations, the Sniders became business partners with members of the Flautt family. This was an association reaching far back through the generations. What could I learn from a detour into the Flautt family history?

A lot, apparently.

In exploring the links listed at Ancestry.com for the Flautt family—and filling in the blanks on the collateral lines in my mother-in-law's family tree as I went—a hint popped up, mentioning one of the inventions patented by a Flautt ancestor: the "Flautt Churn." A photograph of this butter churn was posted to Ancestry by a subscriber. I noticed the photograph was obtained from a book, The Flautt Family in America, written by Mrs. Frank Stough Schwartz.

That, of course, was an invitation to see whether I could find a digitized copy of such a book. Sure enough, it has been uploaded to Internet Archive. And the rabbit trail became even more ensnaring.

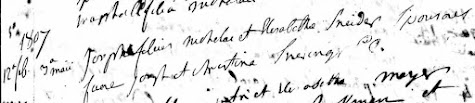

From the book, I gleaned details on the interconnected Catholic parishes such as Conewago in Adams County, Pennsylvania, and Emmitsburg churches in Frederick County, Maryland, as I followed the life of Flautt progenitor Joseph Flautt from his earliest American records in 1769.

Much as Nicholas Schneider had done, Joseph Flautt sold his properties in Adams County, Pennsylvania, and followed his sons to Emmitsburg, a "growing Catholic settlement" on the road to Baltimore. From this resource, I gleaned titles to other history books on the area, the growth of Catholic settlements in the region, and histories of the Flautt family and related lines.

A detail which grabbed me, from page 34 of the book, came from a letter sent by a Flautt descendant to the book's author: "Some one along the way has told us that we came from Alsace-Lorraine."

And later, from page 104, reporting on a 1903 letter from a Flautt descendant:

Our people came from the German side of the Rhine whilst some of them came from the French side and those of the German side spelled their name Flautt as correct for the Germans and Floyd for the French...my grandfather moved across from France to the German side and they would spell his name Flautt whilst these remaining in France spell Floyd.

Reading history books drawn up in earlier years certainly serves to widen our perspective. Just following the history of another family among Nicholas Schneider's F.A.N. Club associates in Maryland and Pennsylvania helped direct me to additional resources, not to mention clues about his European origins. But there are still questions.

If Nicholas Schneider and his supposed F.A.N. Club arrived in Perry County from Emmitsburg, Maryland, and before that, from Adams County, Pennsylvania, I still have to wonder: where did they live before then? After all, the Schneiders arrived in the New World at the port of Philadelphia. Where were they before that point in Adams County, Pennsylvania?

.jpg)